PAINTING OF ITALY

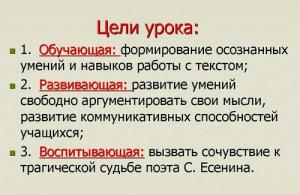

In Italy, where the Catholic reaction finally triumphed in the 17th century, Baroque art was formed very early, flourished and became the dominant movement.

The painting of this time was characterized by spectacular decorative compositions, ceremonial portraits depicting arrogant nobles and ladies with a proud posture, drowning in luxurious clothes and jewelry.

Instead of a line, preference was given to a picturesque spot, mass, and light and shadow contrasts, with the help of which the form was created. Baroque violated the principles of dividing space into plans, the principles of direct linear perspective to enhance depth, the illusion of going into infinity.

The origin of Baroque painting in Italy is associated with the work of the Carracci brothers, the founders of one of the first art schools in Italy - the “Academy of those on the right path” (1585), the so-called Bologna Academy - a workshop in which novice masters were trained according to a special program.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) was the most talented of the three Carracci brothers. His work clearly shows the principles of the Bologna Academy, which set as its main task the revival of monumental art and the traditions of the Renaissance during its heyday, which Carracci’s contemporaries revered as an example of unattainable perfection and a kind of artistic “absolute”. Therefore, Carracci perceives the masterpieces of his great predecessors more as a source from which one can draw aesthetic solutions found by the titans of the Renaissance, and not as a starting point for his own creative quests. The plastically beautiful, the ideal is not for him the “highest degree” of the real, but only an obligatory artistic norm - art is thus opposed to reality, in which the master does not find a new fundamental ideal. Hence the conventionality and abstractness of his images and pictorial solutions.

At the same time, the art of the Carracci brothers and Bolognese academicism turned out to be extremely suitable for being placed in the service of official ideology; it is not without reason that their work quickly received recognition in the highest (state and Catholic) spheres.

Largest work Annibale Carracci in the field of monumental painting - painting the gallery of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome with frescoes telling about the life of the gods - based on scenes from the "Metamorphoses" of the ancient Roman poet Ovid (1597-1604, done together with his brother and assistants).

The painting consists of individual panels gravitating towards a central large composition depicting “The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne”, which introduces an element of dynamics into the pictorial ensemble. The naked male figures placed between these panels imitate sculpture, while at the same time being the protagonists of the paintings. The result was an impressive large-scale work, spectacular in appearance, but not united by any significant idea, without which the monumental ensembles of the Renaissance were unthinkable. In the future, these principles embodied by Carracci - the desire for dynamic composition, illusionistic effects and self-sufficient decorativeness - will be characteristic of all monumental painting of the 17th century.

Annibale Carracci wants to fill the motifs taken from the art of the Renaissance with lively, modern content. He calls for studying nature; in the early period of his creativity, he even turned to genre painting. But, from the master’s point of view, nature itself is too rough and imperfect, so on the canvas it should appear already transformed, ennobled in accordance with the norms of classical art. Therefore, specific life motives could exist in the composition only as a separate fragment designed to enliven the scene. For example, in the painting “The Bean Eater” (1580s), one can feel the artist’s ironic attitude towards what is happening: he emphasizes the spiritual primitiveness of the peasant greedily eating beans; images of figures and objects are deliberately simplified. Other genre paintings by the young painter are in the same spirit: “The Butcher’s Shop”, “Self-Portrait with Father”, “Hunting” (all from the 1580s) - adj., fig. 1.

Many of Annibale Carracci's paintings have religious themes. But the cold perfection of forms leaves little room for the manifestation of feelings in them. Only in rare cases does an artist create works of a different kind. This is the Lamentation of Christ (c. 1605). The Bible tells how holy worshipers of Christ came to worship at his tomb, but found it empty. From an angel sitting on the edge of the sarcophagus, they learned about his miraculous resurrection and were happy and shocked by this miracle. But the imagery and emotion of the ancient text do not find much response in Carracci; he could only contrast the light, flowing clothes of the angel with the massive and static figures of the women. The coloring of the picture is also quite ordinary, but at the same time it is distinguished by its strength and intensity.

A special group consists of his works on mythological themes, which reflected his passion for the masters of the Venetian school. In these paintings, glorifying the joy of love, the beauty of the naked female body, Annibale reveals himself as a wonderful colorist, lively and poetic artist.

Among the best works of Annibale Carracci are his landscape works. Carracci and his students created, based on the traditions of the Venetian landscape of the 16th century, a type of so-called classical, or heroic, landscape. The artist also transformed nature in an artificially sublime spirit, but without external pathos. His works laid the foundation for one of the most fruitful trends in the development of landscape painting of this era (“Flight into Egypt,” ca. 1603), which then found its continuation and development in the work of masters of subsequent generations, in particular Poussin.

Michelangelo Caravaggio (1573-1610). The most significant Italian painter of this period was Michelangelo Caravaggio, who can be considered one of the greatest masters of the 17th century.

The artist's name comes from the name of the town in northern Italy in which he was born. From the age of eleven he already worked as an apprentice to one of the Milanese painters, and in 1590 he left for Rome, which by the end of the 17th century had become the artistic center of all of Europe. It was here that Caravaggio achieved his most significant success and fame.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, who perceived only a more or less familiar set of aesthetic values, Caravaggio managed to abandon the traditions of the past and create his own, deeply individual style. This was partly the result of his negative reaction to the artistic cliches of the time.

Having never belonged to a particular art school, in his early works he contrasted the individual expressiveness of the model, simple everyday motifs with the idealization of images and the allegorical interpretation of the plot characteristic of the art of mannerism and academicism (“Little Sick Bacchus”, “Young Man with a Basket of Fruits”, both - 1593).

Although at first glance it may seem that he departed from the artistic canons of the Renaissance, moreover, he overthrew them, in reality the pathos of his realistic art was their internal continuation, which laid the foundations of realism of the 17th century. This is clearly evidenced by his own statements. “Every picture, no matter what it depicts, and no matter who it was painted,” asserted Caravaggio, “is no good if all its parts are not executed from life; Nothing could be preferred to this mentor.” This statement by Caravaggio, with his characteristic straightforwardness and categoricalness, embodies the entire program of his art.

The artist made a great contribution to the development of the everyday genre (“Rounders,” 1596; “Boy Bitten by a Lizard,” 1594). The heroes of most of Caravaggio’s works are people from the people. He found them in the motley crowd of the street, in cheap taverns and in noisy city squares, and brought them to his studio as models, preferring precisely this method of work to the study of ancient statues - this is evidenced by the artist’s first biographer D. Bellori. His favorite characters are soldiers, card players, fortune tellers, musicians (“Fortune Teller”, “Lute Player” (both 1596); “Musicians”, 1593) - adj., fig. 2. It is they who “inhabit” Caravaggio’s genre paintings, in which he asserts not just the right to exist, but also the artistic significance of a private everyday motif. If in his early works Caravaggio’s painting, for all its plasticity and substantive persuasiveness, was still somewhat rough, then later he gets rid of this shortcoming. The artist’s mature works are monumental canvases with exceptional dramatic power (“The Calling of the Apostle Matthew” and “The Martyrdom of the Apostle Matthew” (both 1599-1600); “Entombment”, “Death of Mary” (both ca. 1605-1606 )). These works, although close in style to his early genre scenes, are already filled with a special internal drama.

Caravaggio's painting style during this period was based on powerful contrasts of light and shadow, expressive simplicity of gestures, energetic sculpting of volumes, richness of color - techniques that create emotional tension, emphasizing the acute affectation of feelings. Usually the artist depicts several figures, taken in close-up, close to the viewer and painted with all plasticity, materiality and visible authenticity. The environment, everyday interiors and still life begin to play a large role in his works. This is how, for example, in the painting “The Calling of Matthew” the master shows the emergence of the sublime and spiritual into the world of “low” everyday life.

The plot of the work is based on the story from the Gospel about how Christ called the tax collector Matthew, despised by everyone, to become his disciple and follower. The characters are depicted sitting at a table in an uncomfortable, empty room, and the characters are presented in life-size, dressed in modern costumes. Christ and the Apostle Peter unexpectedly entering the room evoke a variety of reactions from those gathered - from amazement to wariness. The stream of light entering the dark room from above rhythmically organizes what is happening, highlighting and connecting its main elements (the face of Matthew, the hand and profile of Christ). By snatching figures from the darkness and sharply juxtaposing bright light and deep shadow, the painter gives a feeling of internal tension and dramatic excitement. The scene is dominated by the elements of feelings and human passions. To create an emotional atmosphere, Caravaggio masterfully uses rich color. Unfortunately, Caravaggio’s harsh realism was not understood by many of his contemporaries, adherents of “high art.” After all, even when creating works on mythological and religious themes (the most famous of them is “Rest on the Flight into Egypt”, 1597), he invariably remained faithful to the realistic principles of his everyday painting, therefore even the most traditional biblical subjects received a completely different intimate psychological interpretation different from the traditional one. And the appeal to nature, which he made the direct object of depiction of his works, and the truthfulness of its interpretation caused many attacks on the artist from the clergy and officials.

Nevertheless, among the artists of the 17th century there was, perhaps, not a single one of any significance who would not, in one way or another, have experienced the powerful influence of Caravaggio’s art. True, most of the master’s followers, who were called Caravaggists, diligently copied only his external techniques, and above all, his famous contrasting chiaroscuro, intensity and materiality of painting.

Peter Paul Rubens, Diego Velazquez, Jusepe de Ribera, Rembrandt van Rijn, Georges de La Tour and many other famous artists went through the stage of fascination with Caravaggism. It is impossible to imagine the further development of realism in the 17th century without the revolution that Michelangelo Caravaggio made in European painting.

Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749). His work is associated with the romantic movement in Italian art of the 17th century.

The future artist was born in Genoa. He studied first with his father, then, after his death, in Milan with one of the local masters, who taught him technical techniques Venetian painting and taught the art of portraiture. Subsequently, Magnasco worked for many years in Milan, Genoa, Florence, and only in his declining years, in 1735, did he finally return to his hometown.

This talented but extremely controversial artist was endowed with an extremely bright personality. Magnasco’s work defies any classification: sometimes deeply religious, sometimes blasphemous; in his works he showed himself either as an ordinary decorator or as a painter with a tremulous soul. His art is imbued with heightened emotionality, on the verge of mysticism and exaltation.

The nature of the artist's early works, completed during his stay in Milan, was determined by the traditions of the Genoese school of painting, which gravitated towards the pastoral. But already such works of his as several “Bacchanalia”, “Bandits’ Rest” (all from the 1710s) - depicting restless human figures against the backdrop of majestic ancient ruins - carry a completely different emotional charge than the serene pastorals of his predecessors. They are made in dark colors, with choppy, dynamic strokes, indicating the perception of the world in a dramatic aspect (add., Fig. 3).

The artist’s attention is drawn to everything unusual - scenes of the Inquisition tribunals, torture, which he could observe in Milan under Spanish rule (“Torture Chamber”), a sermon in a synagogue (“Synagogue”, late 1710s-1720s), nomadic life gypsies (“Gypsy Meal”), etc.

Magnasco’s favorite subjects are various episodes from monastic life (“Funeral of a Monk”, “Nuns’ Meal”, both from the 1720s), cells of hermits and alchemists, ruins of buildings and night landscapes with figures of gypsies, beggars, wandering musicians, etc. Quite real. the characters of his works - bandits, fishermen, hermits, gypsies, comedians, soldiers, washerwomen (Landscape with Washerwomen, 1720s) - act in a fantastic environment. They are depicted against the backdrop of gloomy ruins, a raging sea, wild forest, harsh gorges. Magnasco paints their figures as exaggeratedly elongated, as if writhing and in constant, continuous movement; their elongated curved silhouettes are subordinated to the nervous rhythm of the brushstroke. The paintings are permeated with a tragic feeling of human insignificance in the face of the blind forces of nature and the harshness of social reality.

The same disturbing dynamics distinguishes his landscape sketches, with their emphasized subjectivity and emotionality, pushing into the background the transfer of real pictures of nature (“Seascape”, 1730s; “Mountain Landscape”, 1720s). In some of the master's later works, the influence of landscapes by the Italian Salvatore Rosa and engravings by the French Mannerist artist Jacques Callot is noticeable. This hard-to-distinguish facet of reality and the bizarre world created by the imagination of the artist, who acutely felt all the tragic and joyful events of the surrounding reality happening around him, will always be present in his works, giving them the character of either a parable or an everyday scene.

Magnasco's expressive painting style in some ways anticipated the creative quests of 18th-century artists. He paints with fluent, rapid strokes, using restless chiaroscuro, giving rise to restless lighting effects, which gives his paintings a deliberate sketchiness, and sometimes even decorativeness. At the same time, the coloring of his works is devoid of colorful multicolor; usually the master is limited to a gloomy grayish-brown or greenish palette, although in its own way quite refined and refined. Recognized during his lifetime and forgotten by his descendants, this unique artist regained popularity only at the beginning of the 20th century, when he was seen as a forerunner of impressionism and even expressionism.

Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747), a native of Bologna, began his painting career by diligently copying paintings and frescoes by famous masters, including his fellow countrymen the Carracci brothers. Later, he traveled around northern Italy, becoming acquainted with the work of the High Renaissance masters, mainly Venetian (Titian and Veronese).

By the beginning of the 18th century. Crespi is already quite famous, in particular, for his altar images. But the main work of the early period of his work is the monumental painting of lampshades of the Palazzo Count Pepoli (1691-1692) in Bologna, the mythological characters of which (gods, heroes, nymphs) in his interpretation look extremely earthly, animated and convincing, in contrast to the traditional abstract images of the Baroque .

Crespi worked in various genres. He painted on mythological, religious and everyday subjects, created portraits and still lifes, and brought a new and sincere vision of the contemporary world to each of these traditional genres. The artist’s commitment to nature and an accurate representation of the surrounding reality came into irreconcilable contradiction with the decrepit traditions of Bolognese academicism, which by this time had become a brake on the development of art. Therefore, a constant struggle against the conventions of academic painting for the triumph of realistic art runs like a red thread through all of his work.

In the early 1700s. Crespi moves from mythological scenes to depicting scenes from peasant life, treating them first in the spirit of pastoralism, and then giving them the increasingly convincing character of everyday painting. One of the first among the masters of the 18th century, he began to depict the life of ordinary people - laundresses, dishwashers, cooks, as well as episodes from peasant life.

The desire to give his paintings greater authenticity forces him to turn to Caravaggio’s “funeral” light technique - sharp illumination of part of the dark space of the interior, thanks to which the figures acquire plastic clarity. The simplicity and sincerity of the narrative are complemented by the inclusion of folk items into the interior depiction, which are always painted by Crespi with great artistic skill (“Scene in the Cellar”; “Peasant Family”).

The highest achievement of everyday painting of that time were his canvases “Fair in Poggio a Caiano” (c. 1708) and “Fair” (c. 1709) depicting crowded folk scenes.

They showed the artist’s interest in the graphics of Jacques Callot, as well as his close acquaintance with the work of the Dutch masters of genre painting of the 17th century. But Crespi’s images of peasants lack Callot’s irony, and he is not as skilled at characterizing the environment as the Dutch genre painters did. The figures and objects in the foreground are drawn in more detail than the others - this is reminiscent of Magnasco’s style. However, the works of the Genoese painter, executed in a bravura manner, always contain an element of fantasy. Crespi strove for a detailed and accurate story about a colorful and cheerful scene. Clearly distributing light and shadow, he endows his figures with vital specificity, gradually overcoming the traditions of the pastoral genre.

The most significant work of the mature master was the series of seven paintings “Seven Sacraments” (1710s) - the highest achievement of Baroque painting early XVIII centuries (add., Fig. 4). These are completely new works in spirit, which marked a departure from the traditional abstract interpretation of religious scenes.

All paintings (“Confession”, “Baptism”, “Marriage”, “Communion”, “Priesthood”, “Confirmation”, “Unction”) are painted in Rembrandt’s warm reddish-brown tonality. The use of harsh lighting adds a certain emotional note to the narrative of the sacraments. The artist’s color palette is rather monochrome, but at the same time surprisingly rich in various shades and tints of colors, united by a soft, sometimes as if glowing from within chiaroscuro. This gives all the depicted episodes a touch of mysterious intimacy of what is happening and at the same time emphasizes Crespi’s plan, who strives to tell about the most significant stages of existence for each person of that time, which are presented in the form of scenes from reality, acquiring the character of a kind of parable. Moreover, this story is distinguished not by the didactics characteristic of the Baroque, but by secular edification.

Almost everything that was written by the master after this presents a picture of the gradual fading of his talent. Increasingly, he uses familiar cliches, compositional schemes, and academic poses in his paintings, which he previously avoided. It is not surprising that soon after his death Crespi's work was quickly forgotten.

As a bright and original master, he was discovered only in the twentieth century. But in its quality, depth and emotional richness, Crespi’s painting, which completes the art of the 17th century, in its best manifestations is second, perhaps, only to Caravaggio, with whose work Italian art of this era began so brilliantly and innovatively.

This text is an introductory fragment. From the book Broken Life, or Oberon's Magic Horn author Kataev Valentin PetrovichPainting Mom bought me something like an album that unfolded like a harmonica, in zigzags; on its very thick cardboard pages were printed in paint many images of randomly scattered various household items: a lamp, an umbrella, a briefcase,

From the book Tamerlane by Roux Jean-PaulPainting From the fact of the creation of the Book Academy in Herat by Shahrukh and his son, the philanthropist Bai Shungkur (d. 1434), it is clear that at the beginning of the 15th century, a book written in elegant calligraphic handwriting, beautifully bound and illustrated with miniatures, was used

From the book Kolyma notebooks author Shalamov VarlamPainting Portrait is an ego dispute, a dispute, Not a complaint, but a dialogue. The battle of two different truths, the battle of brushes and lines. A stream, where rhymes are colors, Where every Malyavin is Chopin, Where passion, without fear of publicity, Destroyed someone's captivity. In comparison with any landscape, where confession is in

From the book Reflections on Writing. My life and my era by Henry Miller From the book My Life and My Epoch by Henry MillerPainting It is important to master the basics of the skill, and in old age to gain courage and paint what children draw, not burdened with knowledge. My description of the painting process is that you are looking for something. I think any creative work is something like that. In music

From the book by Renoir by Bonafou PascalChapter Seven ROWERS OF CHATOU, PAINTING OF ITALY His friends treated Renoir, who exhibited at the Salon, condescendingly, not considering him a “traitor.” The fact is that Cezanne and Sisley were also “renegades”, since they decided not to take part in the fourth exhibition of “independent artists”

From the book Matisse by Escolier RaymondJUDGMENT AND PAINTING Nothing, it would seem, prevented Henri Matisse, who received a classical education, from realizing his father's plans, and his father wanted him to become a lawyer. Having easily passed the exam in Paris in October 1887, which allowed him to devote himself to

From the book Churchill without lies. Why do they hate him? by Bailey BorisChurchill and painting In 1969, Clementine told Martin Gilbert, the author of the most fundamental biography of Churchill in eight volumes (the first two volumes were written by Churchill’s son Randolph): “The failure in the Dardanelles haunted Winston all his life. After leaving

From the book Great Men of the 20th Century author Vulf Vitaly YakovlevichPainting

From the book Diary Sheets. Volume 2 author Roerich Nikolai KonstantinovichPainting First of all, I was drawn to paints. It started with oil. The first paintings were painted very thickly. No one thought that you can cut perfectly with a sharp knife and get a dense enamel surface. That’s why “The Elders Converge” came out so rough and even sharp. Someone in

From Rachmaninov's book author Fedyakin Sergey Romanovich5. Painting and music “Island of the Dead” is one of Rachmaninov’s darkest works. And the most perfect. He will begin writing it in 1908. He would finish at the beginning of 1909. Once upon a time, in the slow movement of an unfinished quartet, he anticipated the possibility of such music. Long,

From Jun's book. Loneliness of the sun author Savitskaya SvetlanaPainting and graphics To learn to draw, you must first learn to see. Anyone can paint, both a camera and a mobile phone can copy, but, as is believed in painting, the “artist’s face” is difficult to achieve. Juna left her mark in painting. Her paintings

From the book History of Art of the 17th Century author Khammatova V.V.PAINTING OF SPAIN The art of Spain, like the entire Spanish culture as a whole, was distinguished by its significant originality, which consists in the fact that the Renaissance in this country, having barely reached the stage of high prosperity, immediately entered a period of decline and crisis, which were

From the author's bookPAINTING OF FLANDERS Flemish art in some sense can be called a unique phenomenon. Never before in history has such a small country in area, which was also in such a dependent position, created such an original and significant country in its own right.

From the author's bookPAINTING OF THE NETHERLANDS The Dutch revolution turned Holland, in the words of K. Marx, “into an exemplary capitalist country of the seventeenth century.” Conquest of national independence, destruction of feudal remnants, rapid development of productive forces and trade

From the author's bookPAINTING OF FRANCE France occupied a special place among the leading European countries in the field of artistic creativity in the 17th century. In the division of labor among national schools of European painting in solving genre, thematic, spiritual and formal problems, the share of France

Chapter "Art of Italy". Section "Art of the 17th century". General history of art. Volume IV. Art of the 17th and 18th centuries. Authors: V.E. Bykov (architecture), V.N. Grashchenkov (fine arts); under the general editorship of Yu.D. Kolpinsky and E.I. Rotenberg (Moscow, State Publishing House "Art", 1963)

The victory of the feudal-Catholic reaction, the economic and political upheavals that befell the 16th century. Italy, put an end to the development of Renaissance culture. The attack of militant Catholicism on the gains of the Renaissance was marked by the most severe persecution of people of advanced science and an attempt to subordinate art to the power of the Catholic Church. The Inquisition mercilessly dealt with everyone who directly or indirectly opposed the tenets of religion, the papacy and the clergy. Fanatics in robes send Giordano Bruno to the stake and pursue Galileo. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) made special decrees regulating religious painting and music, aimed at eradicating the secular spirit in art. Founded in 1540, the Jesuit order actively intervenes in matters of art, placing art in the service of religious propaganda.

By the beginning of the 17th century. The nobility and the church in Italy consolidate their political and ideological positions. The situation in the country remains difficult. The oppression of the Spanish monarchy, which captured the Kingdom of Naples and Lombardy, is further intensified, and the territory of Italy, as before, remains the scene of continuous wars and robberies, especially in the north, where the interests of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs and France collided (as evidenced, for example, by the capture and the sack of Mantua by imperial troops in 1630). Fragmented Italy is actually losing its national independence, having long ago ceased to play an active role in the political and economic life of Europe. Under these conditions, the absolutism of small principalities acquired features of extreme reactionary behavior.

Popular anger against the oppressors erupts in spontaneous uprisings. At the very end of the 16th century. the remarkable thinker and scientist Tommaso Campanella became the head of an anti-Spanish conspiracy in Calabria. As a result of betrayal, the uprising was prevented, and Campanella himself, after terrible torture, was sentenced to life imprisonment. In his famous essay “City of the Sun,” written in prison, he sets out the ideas of utopian communism, reflecting the dream of an oppressed people about a happy life. In 1647, a popular uprising broke out in Naples, and in 1674 in Sicily. The Neapolitan uprising, led by the fisherman Masaniello, was especially formidable. However, the fragmented nature of the revolutionary actions doomed them to failure and defeat.

The plight of the people contrasts sharply with the overflowing luxury of the landed and monetary aristocracy and the high-ranking clergy. Lush festivities, carnivals, construction and decoration of palaces, villas and churches reached the 17th century. unprecedented scope. All the life and culture of Italy in the 17th century. woven from sharp contrasts and irreconcilable contradictions, reflected in the contradictions of progressive science, in the clash of secular culture and Catholic reaction, in the struggle between conventionally decorative and realistic tendencies in art. A renewed interest in antiquity coexists with the preaching of religious ideas; sober rationalism of thinking is combined with a craving for the irrational and mystical. Along with achievements in the field of exact sciences, astrology, alchemy, and magic are flourishing.

The popes, who ceased to claim the role of the leading political force in European affairs and turned into the first sovereign sovereigns of Italy, use trends towards the national unification of the country and the centralization of power to strengthen the ideological dominance of the church and the nobility. Papal Rome becomes the center of not only Italian, but also European feudal-Catholic culture. Baroque art was formed and flourished here.

One of the main tasks of Baroque artists was to surround secular and ecclesiastical authorities with an aura of greatness and caste superiority, and to propagate the ideas of militant Catholicism. Hence the typical Baroque desire for monumental elation, large decorative scope, exaggerated pathos and deliberate idealization in the interpretation of images. In Baroque art, there are acute contradictions between its social content, designed to serve the ruling elite of society, and the need to influence the broad masses, between the conventionality of images and their emphatically sensual form. In order to enhance the expressiveness of images, Baroque masters resorted to all kinds of exaggeration, hyperbole and naturalistic effects.

The harmonious ideal of Renaissance art was replaced in the 17th century. an attempt to reveal images through a dramatic conflict, by deepening them psychologically. This led to the expansion of the thematic range in art, to the use of new means of figurative expression in painting, sculpture and architecture. But the artistic achievements of Baroque art were achieved at the cost of abandoning the integrity and completeness of the worldview of the people of the Renaissance, at the cost of abandoning the humanistic content of the images.

The autonomy of each art form inherent in the art of the Renaissance, their equal relationship with each other, is now being destroyed. Subject to architecture, sculpture and painting organically merge into one common decorative whole. Painting seeks to illusorily expand the space of the interior; sculptural decor, growing out of architecture, turns into picturesque decoration; The architecture itself either becomes increasingly plastic, losing its strict architectonics, or, dynamically forming internal and external space, acquires the features of picturesqueness.

In the Baroque synthesis of arts, there is not only a merging of individual types of art, but also a merging of the entire artistic complex with the surrounding space. Sculptural figures appear as if alive from niches, hanging from cornices and pediments; the interior space of the buildings continues with the help of illusionistically interpreted lampshades. The internal forces inherent in architectural volumes seem to find their way out in the colonnades, staircases, terraces and trellises adjacent to the building, in decorative sculptures, fountains and cascades, in the receding perspectives of the alleys. Nature, transformed by the skillful hand of a park decorator, becomes an integral part of the Baroque ensemble.

This desire of art for a wide scope and universal artistic transformation of the surrounding reality, limited, however, to the solution of externally decorative tasks, is to some extent consonant with the advanced scientific worldview of the era. Giordano Bruno's ideas about the universe, its unity and infinity revealed new horizons to human knowledge and posed the eternal problem of the world and man in a new way. In turn, Galileo, continuing the traditions of the Empirical Science of the Renaissance, moved from the study of individual phenomena to the knowledge of the general laws of physics and astronomy.

The Baroque style had analogues in Italian literature and music. A typical phenomenon of the era was Marine’s pompous, gallant and erotic lyrics and the whole movement in poetry that he spawned, the so-called “Marinism”. The gravity of artistic culture of the 17th century. to the synthetic unification of various types of art received a response in the brilliant flowering of Italian opera and the emergence of new musical genres - cantata and oratorio. In the Roman opera of the 1630s, that is, the period of mature Baroque, decorative entertainment acquired great importance, subordinating both singing and instrumental music. They are even trying to stage purely religious operas, full of ecstatic pathos and miracles, when the action covers the earth and sky, just as it was done in painting. However, like literature, where Marinism faced classicist opposition and was ridiculed by advanced satirical poets, opera very soon went beyond the boundaries of court culture, expressing more democratic tastes. This was reflected in the penetration of folk song motifs into the opera and the cheerful entertainingness of the plot in the spirit of commedia dell'arte (comedy of masks).

Thus, although Baroque is the dominant movement for Italy in the 17th century, it does not cover the entire diversity of cultural and artistic phenomena of this time. The realistic art of Caravaggio, which reveals the painting of the 17th century, acts as the direct opposite of the entire Baroque aesthetics. Despite social conditions unfavorable for the development of realism, genre-realistic trends in painting made themselves felt throughout the 17th century.

In all Italian fine art of the 17th century. One can name only two great masters of pan-European significance - Caravaggio and Bernini. In a number of its manifestations, Italian art of the 17th century. bears a specific imprint of the decline of social life, and it is very significant that Italy, earlier than other countries, came up with a new realistic program in painting, turned out to be unable to implement it consistently. Incomparably brighter than painting, historical significance has Italian architecture, which, along with French, occupies a leading place in European architecture of the 17th century.

In the fine arts, as in the architecture of Italy, in the 17th century the Baroque style gained dominant significance. It arises as a reaction against “mannerism”, the far-fetched and complex forms of which are opposed, first of all, by the great simplicity of images, drawn both from the works of the masters of the High Renaissance, and due to independent study of nature. Keeping a keen eye on the classical heritage, often borrowing individual elements from it, the new direction strives for the greatest possible expressiveness of forms in their rapid dynamics. New painting techniques also correspond to the new searches of art: the calm and clarity of the composition are replaced by their freedom and, as it were, randomness. The figures are shifted from their central position and are built in groups mainly according to diagonal lines. This construction is important for the Baroque. It enhances the impression of movement and contributes to a new transfer of space. Instead of dividing it into separate layers, usual for Renaissance art, it is covered by a single glance, creating the impression of a random fragment of an immense whole. This new understanding of space belongs to the most valuable achievements of the Baroque, which played a certain role in the further development of realistic art. The desire for expressiveness and dynamics of forms gives rise to another feature, no less typical of the Baroque - the use of all kinds of contrasts: contrasts of images, movements, contrasts of illuminated and shadow plans, color contrasts. All this is complemented by a pronounced desire for decorativeness. At the same time, the pictorial texture is also changing, moving from a linear-plastic interpretation of forms to an increasingly broader picturesque vision.

The noted features of the new style acquired more and more specific features over time. This justifies the division of 17th-century Italian art into three unevenly lasting stages: the “early”, “mature” or “high”, and the “late” Baroque, whose dominance lasts much longer than the others. These features, as well as chronological limits, will be noted below.

The Baroque art of Italy serves mainly the dominant Catholic Church, established after the Council of Trent, the princely courts and the numerous nobility. The tasks set before the artists were as much ideological as decorative. The decoration of churches, as well as palaces of the nobility, monumental paintings of domes, lampshades, and walls using the fresco technique are receiving unprecedented development. This type of painting became the specialty of Italian artists who worked both in their homeland and in Germany, Spain, France, and England. They retained undeniable priority in this area of creativity until the end of the 18th century. The themes of church paintings are lush scenes glorifying religion, its dogmas or saints and their deeds. The plafonds of the palaces are dominated by allegorical and mythological subjects, serving as glorification of the ruling families and their representatives.

Large altar paintings are still extremely common. In them, along with the solemnly majestic images of Christ and the Madonna, images that had the most powerful impact on the viewer are especially common. These are scenes of executions and tortures of saints, as well as their states of ecstasy.

Secular easel painting most willingly took on themes from the Bible, mythology and antiquity. Landscape, battle genre, and still life are developed as independent types.

36

INTRODUCTION

In the history of Italian literature, the borders of the 17th century. How literary era basically coincide with the borders of the 17th century, although, of course, not absolutely accurately.

In 1600, in Rome, in the Piazza des Flowers, Giordano Bruno was burned. He was the last great writer of the Italian Renaissance. But Rome, surrounding Bruno’s fire, was already densely built up with Baroque churches. A new artistic style arose in the depths of the previous century. It was a long and gradual process. However, there was also a kind of “break in gradualism” in it, a transition to a new quality. Despite the fact that individual and quite impressive symptoms of the Baroque were observed in Italy throughout the second half of the 16th century, “the real turning point occurred at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, and simultaneously in many arts - architecture, painting, music. And although the remnants of mannerism in Italy still continue to be felt in the first and even the second decade of the 17th century, in essence, the overcoming of mannerism in Italy can be considered completed by 1600” (B. R. Wipper).

By 1600, many Italian writers of the 17th century. - Campanella, Sarpi, Galileo, Boccalini, Marino, Chiabrera, Tassoni - were already

fully formed writers; however, the most significant works of Baroque and Classicism were created by them only in the first decades of the new century. The line between the two eras is clearly drawn, and it was already visible to contemporaries. The “gap of gradualism” was reflected in the self-consciousness of culture and gave rise to a sharp contrast between modernity and the past, not only from Greco-Roman antiquity, but also from the classical Renaissance. “New”, “modern” became at the beginning of the 17th century. fashionable words. They become a kind of battle cry with which traditions are attacked and authority is overthrown. Galileo publishes discourses on the “new sciences”; Chiabrera speaks of the desire, like his fellow countryman Columbus, to “discover new lands” in poetry; the most popular poet of the century, Marino, declares that he does not at all smile at “standing on a par with Dante, Petrarch, Fra Guittone and others like them,” because his goal is to “delight the living,” and the esthetician Tesauro assures that he is contemporary with him literary language far surpassed the language of the great trecentists - Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. At the beginning of the 17th century. Italian writers often talk about the superiority of their era over past times, about the rapid growth of human knowledge, about the absoluteness of progress. The most striking expression of the new attitude towards established authorities and traditions was found in the works of Alessandro Tassoni, poet, publicist and one of the most brilliant literary critics XVII century His “Reflections on the Poems of Petrarch” (1609) and especially the ten books of “Various Thoughts” (1608-1620) are an important link in the preparation of the “dispute about ancient and modern authors” that will unfold in France at the end of the 17th century.

At first glance, it may seem that with their glorifications of the New Age, the progress of knowledge and poetry, Italian writers of the 17th century. reminiscent of the Quattrocento humanists - Gianozzo Manetti or Marsilio Ficino. Actually this is not true. Fierce polemics with the past, a feverish search for the new, unusual, extravagant, so characteristic of the entire artistic atmosphere of Italy in the 17th century, do not in themselves serve as a guarantee of the authenticity of the innovation of seichentist literature. On the other hand, denial cultural traditions of the past century does not always imply among Italian writers of the 17th century. an enthusiastic, apologetic attitude towards one’s own time. Equally aware of the deep gap between the 17th century. and the period preceding it, writers such as Tesauro and Campanella had completely different attitudes towards the socio-political reality of contemporary Italy. If the Jesuit Tesauro, with all his baroque “modernism,” was a political conservative who shared the retrograde positions of the Catholic Church, then the incorrigible “heretic” Campanella, with all his medieval religiosity and glance at “ancient times,” became a social reformer who saw even in astronomy signs of the future social cataclysms designed to sweep away the feudal system and establish on its ruins the kingdom of labor, justice and property equality.

Not so sharp, but also fundamental differences in assessments of both modern reality and the content of the “new” in art and literature existed between Chiabrera and Marino, between Tassoni and Lancellotti, between Sarpi and Sforza Pallavicino. In its literary and aesthetic content, the Italian 17th century is a complex period, socially heterogeneous and extremely contradictory. It is incomparably more contradictory than the Renaissance era that preceded it. And this is also reflected in his self-awareness. If the classical Renaissance dialectically removed the contradictions that fed it in the highest, almost absolute harmony of artistic images and ideological syntheses, then the Italian 17th century, on the contrary, in every possible way flaunts the sharpness of its inherent contradictions. He elevates dynamic disharmony to the structural principle of culture and puts antitheticality at the basis of his main, dominant style. In place of the fully developed, “universal man” of the Italian Renaissance, calm, majestic and “divine” in his “naturalness,” in the 17th century. a man of the Italian Baroque comes - a hedonistic pessimist, nervous, painfully restless, extravagant, in a medieval way, torn between spirit and flesh, between “earth” and “heaven”, extremely self-confident and at the same time eternally trembling before the insurmountability of Death and Fortune, hiding his true a face under the guise of a vulgarly bright theatrical mask. In the 17th century even the most advanced and courageous thinkers, who continue the traditions of the Renaissance in new historical conditions, lose that internal integrity that was so characteristic of the titans of the past era.

At the same time, talking about the absolute decline of Italian culture in the 17th century. - as was often done - it is impossible for the mere fact that seichentist Italy continued to remain part of Western Europe, culture

Illustration:

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini.

Ecstasy of St. Teresa

1645-1652

Rome, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria

which at that time was on the rise, compensating for the loss of Renaissance integrity not only with great natural scientific discoveries, but also with significant aesthetic achievements. In the first half of the 17th century. the language of Italian literature was still the language of educated European society, although it had already been somewhat displaced by French and partly Spanish. In some areas of cultural life, Italy continued to maintain a leading position in Europe and even gained new positions. The latter applies primarily to music. In 1600, the poet Ottavio Rinuccini and the composer Jacopo Peri showed in Florence the musical drama “Euridice,” which laid the foundation for opera, or, as they said then, emphasizing the syncretism of the new genre and its inseparability from literature, “melodrama.” “Eurydice” was followed by the great works of Claudio Monteverdi: “Orpheus” (1607), “Ariadne” (1608), “The Coronation of Poppea” (1642). A hitherto unknown world opened up before humanity. In music - operatic as well as instrumental (Frescobaldi, Corelli) - the Italian 17th century left many enduring aesthetic values. Italian music provided the Baroque style - Monteverdi called it “stil concetato”, the style “excited”, “excited” - the same place of honor in European artistic culture that the style of Attic tragedy, French Gothic cathedrals and Italian poetry had previously occupied in it. French and English Renaissance.

Italy has also achieved significant success in the field of fine arts. In architecture, painting and sculpture, the Baroque was formed first of all in Rome, where Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona, and Francesco Borromini worked. From their works, artists from France, Spain, and Germany learned not only decorativeness and pomp, but also new forms of expressiveness, reproduction of movement, intimate and personal experiences, and the ability to capture the life of the human environment even in a sculptural portrait.

One should not, however, think that Italy’s influence on the architecture, sculpture and painting of the rest of Europe was limited in the 17th century. the sphere of courtly aristocratic art. Even more than the example of Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, European artistic culture was influenced by the bold experiments of Annibale Carracci (“The Butcher’s Shop”, “Bean Stew”) and the powerful genius of Caravaggio, whose works were introduced into Italian painting of the 17th century. new aspects of the real world, more democratic themes, situations, images compared to the art of the classical Renaissance. To one degree or another, “Caravaggism” was reflected in the works of almost everyone wonderful artists Spain, Flanders, Holland, and especially those of them who are commonly called the greatest realists of the 17th century. - Velazquez and Rembrandt.

She achieved outstanding achievements in the 17th century. Italian science. To replace the literary academies of the Renaissance, which degenerated in the 17th century. Natural science academies came to the high society salons that turned poetry into fun and buffoonery: the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of Lynxes) in Rome, the Accademia degli Investiganti (Academy of Explorers) in Naples, the Accademia del Cimento (Academy of Experienced Knowledge) in Florence. In the literary life of Italy in the 17th century. they played a role much like that of the Quattrocento philosophical circles. It was with them, as a rule, that the formation of Italian classicism was associated at this time. In this sense, for

Italian 17th century The work of Galileo Galilei, the greatest scientist and greatest writer Seicento, who had no less influence on the formation of Italian national prose than Dante and Machiavelli, is extremely characteristic.

Success Italian musicians, artists and natural scientists did not exclude the possibility that, in general, the culture of seichentist Italy did not rise to the level of the classical Renaissance. In addition, unlike the culture of Holland, England and France, it developed mainly in a descending manner. If at the beginning of the 17th century, when the influence of the Italian Baroque on the literature of Western Europe manifested itself with particular force, Giambattista Marino was not only the idol of the court society of Paris, but could also influence Theophile de Viau and Poussin, then in the 70s the legislator of Western European " good taste" Boileau will say dismissively:

Let's leave it to the Italians

Empty tinsel with its false gloss,

What matters most is the meaning...

The sharp change in artistic tastes, so characteristic of the late 16th - early 17th centuries, reflected the qualitative changes taking place at that time in political, economic and social structures of the entire Italian society. The progress of Italian literature was relative primarily because in the 17th century. Literature in Italy developed in conditions of economic decline and, perhaps more importantly, the social degradation of precisely those social strata that had previously made possible the magnificent and relatively long-lasting flowering of the culture of the Italian Renaissance.

At the end of the 16th century, the feudal-Catholic reaction burst into the economic sphere and received a broad base for its further expansion. The reaction was led by papal Rome, which succeeded in the 17th century. to annex Ferrara and Urbino to its territories, and feudal Spain, which, according to the Cato-Cambresian Peace, became the complete master of most of the Apennine Peninsula. Only Venice and the newly formed Duchy of Savoy retained some political independence in seichentist Italy and, in some cases, resisted the pressure on them from Spain and Rome.

The strengthening of the position of the church and the feudal nobility in the economic and social life of Italy contributed to the expansion of the feudal-Catholic reaction in all spheres of culture. The terror of the Inquisition, begun during the Council of Trent, continued. The Spaniards supported him. Campanella spent many years in prison, he was subjected to brutal torture. In 1616, the holy congregation, by a special decree, prohibited discussing and expounding the teachings of Copernicus. In 1633, the trial of Galileo was arranged. The Spanish governor Pedro Toledo dispersed all scientific societies and literary academies in Naples, with the exception of the Jesuit ones. In the 17th century The Catholic Church and the Spanish authorities continued to see advanced culture as not only an ideological, but also a political enemy.

Nevertheless, in the cultural policy of the feudal-Catholic reaction occurred in the 17th century. some significant qualitative changes that allow us to draw a clear boundary between the 17th century and the Late Renaissance. If in the second half of the 16th century. The Roman Church was primarily occupied with an intense struggle against the “German heresy”, the ruthless

eradicating Renaissance free-thinking and purging its own ranks, then from the beginning of the 17th century it has been making attempts to restore that direct and total influence on science, literature and art that it lost during the Renaissance. The feudal-Catholic reaction begins in the 17th century. to build a culture that meets the vital interests of both the church and the nobility and, at the same time, is capable of influencing the relatively broad masses of the people. She received solid support from the Society of Jesus, which by this time had become a serious social and political force. In the 17th century The Jesuits acquired a monopoly on the upbringing and education of the younger generation and founded their colleges in most of Italy. Almost everywhere their schools became centers for the propaganda of counter-reformation ideas and views. It was from the ranks of the Jesuits that came most of the preachers, thinkers and writers who created that part of Italian literature that can be called the official literature of the feudal-Catholic reaction. This type of literature should include, first of all, various manifestations of religious eloquence, which flourished extremely in Italy throughout the 17th century. and acquired, especially in the work of the Jesuit Paolo Segneri (1624-1694), the features of a typically seichentist genre. This genre adopted the poetics of the Baroque, developed its own theory (treatises by Francesco Panigarolo and Tesauro) and, not limiting itself to the framework of church sermons, was transformed into descriptive, so-called “artistic prose”, where form clearly prevailed over content, and the religious theme was developed based on the material of history , geography, ethnography, etc. The most significant representative of “artistic prose” of the 17th century. in the literature of Italy there was Danielo Bartoli (1608-1685), author of the History of the Society of Jesus, “a most skilful and unsurpassed master of periods and phrases of a pretentious and flowery style” (De Sanctis).

The Counter-Reformation widely and, in a certain sense, successfully used the possibilities of the Baroque style to create official, feudal-aristocratic literature that met the interests of both the church and the ruling class. But for the sake of this, the feudal-Catholic reaction had to sacrifice in Italy the moral and religious rigorism that characterized it cultural policy in the second half of the 16th century. The aesthetic theories of the counter-reformation peripatetics, according to which literature and art should set themselves primarily religious and educational tasks, were replaced in the 17th century. concepts of aesthetic hedonism. The same ideologists of the Italian Counter-Reformation, who, it would seem, just recently were outraged by the blasphemous nudity of the Last Judgment, now provided patronage to artists who introduced not just emphatically sensual, but also openly erotic motifs into their works. And this should not particularly surprise us. This is explained not only by the fact that the Baroque, with its pomp, colorfulness, metaphor and rhetoric, could have a much stronger impact on the imagination of the popular audience than the strict, collected intellectuality of the Renaissance. Another thing turned out to be no less significant: in the works of the aristocratic baroque, sensuality appeared as one of the manifestations of the frailty and illusory nature of the material, “this-worldly” world, and eroticism, paradoxical as it may seem at first glance, turned into a preaching of religious asceticism. This was what made it possible for the Italian Counter-Reformation to use the supposed lack of ideas of the aristocratic baroque to promote its own reactionary ideas, turning the hedonism of marine poetry and prose against the rationalism of new materialist science and philosophy.

Between the feeling of being unsettled

the aristocrat and the picaro's view of the world - the view characteristic of the Neapolitan lumpen - there were certain points of contact, and this explains some of the features of baroque prose, especially baroque burlesque; however, in general, the life ideals of both the Italian peasantry and the Italian urban lower classes came in the 17th century. to antagonistic contradictions with the ideology of the ruling classes. While the former commercial and industrial bourgeoisie was finally becoming a politically cowardly, reactionary class, supporting not only the feudal order, but also the Spanish conquerors, the peasantry and urban lower classes of Italy responded to the ever-increasing social, political and economic oppression with banditry, a “hidden peasant war” (according to F. Braudel), uprisings that were both anti-feudal and anti-Spanish, national liberation in nature. Naples and Palermo became in the 17th century. the main centers not only of the Baroque, but also of popular unrest that did not stop throughout the century. The anti-feudal movement acquired a particularly wide scale in Italy in 1647-1648, when the urban lower classes, led first by the fisherman Tommaso Agnello (Masaniello), and then by the gunsmith Gennare Agnese, seized power in Naples and held it for a year. The Neapolitan uprising was supported by Palermo, where government of the city also passed into the hands of the rebel people for some time, and by a series of peasant riots that swept across southern Italy. In 1674-1676. Sicily was shaken by an anti-Spanish uprising, the center of which this time was Messina. In 1653-1655. The peasants of Savoy rose up in guerrilla warfare against the feudal lords under the banner of the revived Waldensian heresy.

Popular, anti-feudal movements of the 17th century. could not develop in Italy into either a bourgeois revolution, as it happened in England, or into a victorious war of national liberation, as happened in the Netherlands. In Italy of the 17th century. there was no class that could lead the revolutionary struggle against feudalism and bring it to a victorious end. However, this did not mean at all that the protest of the Italian people against their own and foreign oppressors turned out to be completely fruitless, that it was not reflected in Italian literature of the 17th century. and had no influence on the nature of her styles. And the point here is not even that Masaniello’s uprising received a direct response in the satires of Salvator Rosa and in the poems of Antonio Basso, who paid with his life for his active participation in the anti-feudal movement of 1647-1648. The protest of the oppressed people was of much greater importance; it contributed to the formation of Italian literature of the 17th century. from the inside, breaking into the work of not only Sarpi, Tassoni, Boccalini, but also such seemingly very far from politics writers as Giambattista Basile. One of the manifestations of the inconsistency of the Italian 17th century. was that the social development of this time contributed not only to the aristocracy, but also, in a certain sense, to the democratization of Italian literature. If the culture of the Italian Renaissance, the socio-economic base of which was associated mainly with the most developed city-states of the 14th-16th centuries, tended to ignore the peasant, then the so-called refeudalization, by transferring the center of gravity of the Italian economy to the village, made everyone exploited and the oppressed peasant is the figure who passed by in the 17th century. The most sensitive, conscientious and thoughtful representatives of the Italian creative intelligentsia could not pass. The life of the entire Italian society now depended on the peasant, and this was reflected in the aesthetic consciousness of the era.

In the 17th century Not only the folk comedy of masks, which originated in the 16th century, is a fact of Italian national culture. on the periphery of the High Renaissance, but also the fairy tale and the “folk novels” of Giulio Cesare Croce about Bertoldo and Bertoldino, which were based on peasant folklore. Folk art nourished and enriched the Italian Baroque, introducing into it his own aesthetic and life ideals. That is why it is fundamentally wrong to consider the Baroque as a style of the Counter-Reformation and associate it only with the feudal nobility, although the Baroque, indeed, initially arose precisely in those countries where the nobility was the ruling class. And in relation to Italian literature of the 17th century, and in relation to Italian art of this time, we can talk about two trends of the Baroque - aristocratic, reactionary and advanced, folk. That passionate, feverish desire for the new, which, as already noted, was so characteristic of all literature of the Italian 17th century, and especially of the Italian Baroque, was fueled not only by a feeling of a break with the Renaissance and stunning discoveries in physics or astronomy, but also by the desire of the people and peasant masses towards freedom and social justice. It is no coincidence that one of the most important Italian poets of the 17th century.

became Tommaso Campanella, the great writer of the democratic baroque. Explaining the origins of his innovative ideas and daring projects, he told the inquisitors: “I heard complaints from every peasant I met, and from everyone I spoke to, I learned that everyone was inclined to change.” It is the connection between the most significant works of Italian literature of the 17th century. with the people, with their anti-feudal struggle best, apparently explains the fact that even in conditions of almost absolute economic, social and political decline, Italian literature did not lose its national content and continued to create new spiritual values.

In its development, Italian literature XVII V. two large periods passed, the boundary between which falls approximately in the middle of the century. In terms of content, they are not equal to each other. The first period is incomparably richer and more internally intense. It was in the first half of the 17th century. In Italy, classicism was formed, various trends emerged within Baroque literature: Marinism, Chiabreism, the democratic Baroque of Campanella, Basile, Salvator Rosa. By the end of this period, the most important aesthetic treatises were created, formulating the theory of the Baroque.

The second period is characterized by a certain decline of both classicism and Marinism. At this time, the socio-political system was stabilizing in Italy, and after the defeat of the popular movements of the late 40s, the opposition to reaction in literature noticeably weakened. In Italian literature of the second half of the century, the classicist tendency within the Baroque prevails, ultimately degenerating into Rococo. The second period in the literature of Seicento takes place under the sign of the preparation of Arcadia. It ends in 1690, when the creation of this academy marks the beginning of a new stage in the development of Italian poetry, prose and literary theory.

42

Already from the middle of the 16th century, the historical development of Italy was characterized by the advance and victory of the feudal-Catholic reaction. Economically weak, fragmented into separate independent states, Italy is unable to withstand the onslaught of more powerful countries - France and Spain. The long struggle of these states for dominance in Italy ended with the victory of Spain, secured by the peace treaty of Cateau Cambresi (1559). From this time on, the fate of Italy was closely connected with Spain. With the exception of Venice, Genoa, Piedmont and the Papal States, Italy was effectively a Spanish province for almost two centuries. Spain involved Italy in devastating wars, which often took place on the territory of Italian states, and contributed to the spread and strengthening of feudal reaction in Italy both in the economy and in cultural life.

The dominant position in the public life of Italchi was occupied by the aristocracy and the highest Catholic clergy. In the conditions of the deep economic decline of the country, only large secular and ecclesiastical feudal lords still had significant material wealth. The Italian people - peasants and townspeople - were in an extremely difficult situation, doomed to poverty and even extinction. Protest against feudal and foreign oppression finds expression in numerous popular uprisings that broke out throughout the 17th century and sometimes assumed a formidable scale, such as the Masaniello uprising in Naples.

General character The culture and art of Italy in the 17th century was determined by all the features of its historical development. It was in Italy that Baroque art was born and most developed. However, being dominant in Italian art of the 17th century, this direction was not the only one. In addition to it and in parallel with it, realistic movements are developing, associated with the ideology of the democratic strata of Italian society and receiving significant development in many artistic centers of Italy.

Italian art XVII century

The center for the development of new baroque art at the turn of the 16th-17th centuries. was Rome. "Roman Baroque" is the most powerful artistic style in the art of Italy in the second half of the 16th-17th centuries. born primarily in architecture and ideologically connected with Catholicism, with the Vatican. The architecture of this city in the 17th century. seems to be in everything opposite to the classicism of the Renaissance and at the same time firmly connected with it. It is no coincidence that his forerunner is, as already mentioned, Michelangelo.

The Baroque masters break with many of the artistic traditions of the Renaissance, with its harmonious, balanced volumes. Baroque architects included in a holistic architectural ensemble not only individual buildings and squares, but also streets. The beginning and end of the streets are certainly marked by some kind of architectural (squares) or sculptural (monuments) accents. A representative of the early Baroque architect Domenico Fontana (1543-1607), for the first time in the history of urban planning, used a three-ray system of streets diverging from Piazza del Popolo ("People's Square"), thereby achieving a connection between the main entrance to the city and the main ensembles of Rome. Obelisks and fountains placed at the vanishing points of radial avenues and at their ends create an almost theatrical effect of a perspective receding into the distance. The Fountain principle was of great importance for all subsequent European urban planning (remember the three-ray system of St. Petersburg, for example).

The statue as the beginning that organizes the square is replaced by an obelisk with its dynamic upward thrust, and even more often by a fountain, richly decorated with sculpture. A brilliant example of Baroque fountains were Bernini's fountains: "Triton" (1643) in Piazza Barberini and the "Four Rivers" fountain (1648-1651) in Piazza Navona.

At the same time, in the early Baroque era, not only new types of palaces, villas, and churches were created, but the decorative element was strengthened: the interior of many Renaissance palazzos turned into a suite of magnificent chambers, the decor of the portals became more complex, and Baroque masters began to pay a lot of attention to the courtyard and palace garden. The architecture of the villas with their rich garden and park ensemble reached a special scale. As a rule, the same principles of axial construction as in urban planning have developed here: the central access road, the main hall of the villa and the main alley of the park on the other side of the facade run along the same axis. Grottoes, balustrades, sculptures, and fountains abundantly decorate the park, and the decorative effect is further enhanced by the arrangement of the entire ensemble in terraces on a steep terrain.

Lorenzo Bernini. Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona. Rome

The architectural decor became even more magnificent during the mature Baroque period, from the second third of the 17th century. Not only the main facade is decorated, but also the walls on the garden side; from the front lobby you can get directly into the garden, which is a magnificent park ensemble; from the side of the main facade, the side wings of the building extend and form a front courtyard - the so-called cour d'honneur (French cour d "honneur, lit. - court of honor).

In the cult architecture of the mature Baroque, plastic expressiveness and dynamism are enhanced. Numerous openings and breaks of rods, cornices, pediments in sharp light and shadow contrast create an extraordinary picturesque façade. Straight planes are replaced by curved ones, the alternation of curved and concave planes also enhances the plastic effect. The interior of a Baroque church as a place for a magnificent theatrical rite of Catholic service is a synthesis of all types of fine art (and with the advent of the organ, music). Various materials (colored marbles, stone and wood carvings, stucco, gilding), painting with its illusionistic effects - all this, together with the whimsical volumes, created a feeling of the unreal, expanding the space of the temple to infinity. Decorative richness, the sophistication of the play of planes, the invasion of ovals and rectangles instead of the circles and squares beloved by Renaissance masters intensify from one architectural creation to another. It is enough to compare the church of Il Gesu (1575) by Giacomo della Porta (c. 1540-1602) with the church of Sant’Ivo (1642-1660) by Francesco Borromini (1599-1667): here the sharp triangular projections of the walls and the star-shaped dome create an infinitely varied impression, deprives the form of objectivity; or with his own church of San Carlo alle Cuatro Fontane (1634-1667).

Francesco Borromini. Church of Sant'Ivo alla Sanienza. Rome

Francesco Borromini. Church of Sant'Ivo alla Sanienza. Rome

Francesco Boromini. Dome of the Church of San Carlo alle Cuatro Fontane in Rome

Francesco Boromini. Dome of the Church of San Carlo alle Cuatro Fontane in Rome

Sculpture is closely related to architecture. It decorates the facades and interiors of churches, villas, city palazzos, gardens and parks, altars, tombstones, fountains. In Baroque it is sometimes impossible to separate the work of the architect and the sculptor. The artist who combined both talents was Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini(1598-1680). As court architect and sculptor to the popes, Bernini carried out commissions and headed all major architectural, sculptural and decorative works, which were carried out to decorate the capital. Largely thanks to the churches built according to his design, the Catholic capital acquired a Baroque character (Church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale, 1658-1678). In the Vatican Palace, Bernini designed the “Royal Staircase” (Scala regia), which connected the papal palace with the cathedral. He owns the most typical creation of the Baroque - the canopy (ciborium) in St. Peter's Cathedral (1657-1666), dazzling with decorative richness of various materials, unbridled artistic imagination, as well as many statues, reliefs and tombstones of the cathedral. But Bernini's main creation is the grandiose colonnade of St. Peter's Cathedral and the design of the gigantic square near this cathedral (1656-1667). The depth of the area is 280 m; in its center there is an obelisk; fountains on the sides emphasize the transverse axis, and the square itself is formed by a powerful colonnade of four rows of columns of the Tuscan order, nineteen meters high, forming a strict, open circle, “like open arms,” as Bernini himself said.

The colonnade, like a wreath, crowned the cathedral, which was touched by the hand of all the great architects of the Renaissance from Bramante to Raphael, Michelangelo, Baldassare Peruzzi (1481-1536), Antonio da Sangalla the Younger (1483-1546). The last to decorate the main portico was Bramante's student Carlo Maderna (1556-1629).

Lorenzo Bernini. Colonnade of the square in front of St. Peter's Basilica. Rome

Lorenzo Bernini. Colonnade of the square in front of St. Peter's Basilica. Rome

Bernini was an equally famous sculptor. Like the Renaissance masters, he turned to both ancient and Christian subjects. But his image of "David" (1623), for example, sounds different from that of Donatello, Verrocchio or Michelangelo. Bernini's "David" is a "militant plebeian", a rebel; it does not contain the clarity and simplicity of the images of the Quattrocento, or the classical harmony of the High Renaissance. His thin lips are stubbornly compressed, his small eyes are narrowed angrily, his figure is extremely dynamic, his body is almost rotated around its axis.

Bernini created many sculptural altars for Roman churches, tombstones of famous people of his time, fountains in the main squares of Rome (the already mentioned fountains in Piazza Barberini, Piazza Navona, etc.), and in all these works their organic connection with the architectural environment is manifested. Bernini was a typical artist who worked on behalf of the Catholic Church, therefore, in one hundred altarpieces, created with the same decorative brilliance as other sculptural works, the language of baroque plasticity (illusory transfer of the texture of objects, love for the combination of different materials not only in texture, but and but in color, the theatricalization of the action, the general “picturesqueness” of the sculpture) a certain religious idea is always clearly expressed (“The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa of Avila” in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome).

Bernini was the creator of a Baroque portrait in which all the features of the Baroque are fully revealed: this image is ceremonial, theatrical, decorative, but the overall ostentation of the image does not obscure the real appearance of the model (portraits of the Duke d'Ests, Louis XIV).

In the painting of Italy at the turn of the XVI-XVII centuries. two main ones can be distinguished artistic directions: one is associated with the work of the Carracci brothers and received the name “Bolognese academicism”, the other - with the art of one of the most important artists of Italy in the 17th century. Caravaggio.

Annibale and Agostino Carracci and their cousin Lodovico founded the Academy of those who entered the true path (Accademia degli incamminati) in Bologna in 1585, in which artists studied according to a specific program. Hence the name - “Bologna academicism” (or “Bologna school”). The principles of the Bologna Academy, which was the prototype of all European academies of the future, can be traced in the work of the most talented of the brothers - Annibale Carracci (1560-1609).

Carracci carefully studied and studied nature. He believed that nature is imperfect and needs to be transformed, ennobled, in order for it to become a worthy subject of depiction in accordance with classical norms. Hence the inevitable abstraction, rhetorical nature of Carracci’s images, pathos instead of genuine heroism and beauty. Carracci's art turned out to be very timely, consistent with the spirit of the official ideology, and received rapid recognition and dissemination.

Annibale Carracci. Venus and Adonis. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Annibale Carracci. Venus and Adonis. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

The Carracci brothers are masters of monumental and decorative painting. Their most famous work is the painting of the gallery in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome on the subjects of Ovid's "Metamorphoses" (1597-1604), typical of Baroque painting. In addition, Annibale Carracci was the creator of the so-called heroic landscape - an idealized, fictitious landscape, because nature, like man (according to the Bolognese), is imperfect, rough and requires refinement in order to be represented in art. This is a landscape unfolded with the help of scenes in depth, with balanced masses of clumps of trees and almost obligatory ruins, with small figures of people serving only as staff to emphasize the greatness of nature. The coloring of the Bolognese is equally conventional: dark shadows, local, clearly arranged colors, light gliding through the volumes. Carracci's ideas were developed by a number of his students (Guido Reni, Domenichino, etc.), in whose work the principles of academicism were almost canonized and spread throughout Europe.

Michelangelo Merisi(1573-1610), nicknamed Caravaggio (after his place of birth), is an artist who gave the name to a powerful realistic movement in art bordering on naturalism - Caravaggism, which gained followers throughout Western Europe. The only source from which Caravaggio finds it worthy to draw themes of art is the surrounding reality. Caravaggio's realistic principles make him a heir to the Renaissance, even though he subverted classical traditions. Caravaggio's method was the antithesis of academicism, and the artist himself rebelled against it, asserting his own principles. Hence the appeal (not without challenging accepted norms) to unusual characters such as gamblers, sharpers, fortune tellers, various kinds of adventurers, with whose images Caravaggio laid the foundation for everyday painting of a deeply realistic spirit, combining the observational skills of the Dutch genre with the clarity and precision of the form of the Italian school ("The Lute Player", ca. 1595; "Players", 1594-1595).

But the main ones for the master remain religious themes (altar images), which Caravaggio strives to embody with truly innovative courage as life-reliable. In “Evangelist Matthew with an Angel” (1599-1602) the apostle looks like a peasant, he has rough hands familiar with hard work, his wrinkled face is tense from an unusual activity - reading.

Caravaggio. The calling of the Apostle Matthew. Church of San Luigi Dei Francesi in Rome

Caravaggio. The calling of the Apostle Matthew. Church of San Luigi Dei Francesi in Rome