In the folklore version of the fairy tale “Turnip”, recorded by the researcher Afanasyev (1826-1871),

Feet take part in pulling turnips out of the ground: “A friend’s foot came; each other's legs..."

Image: John Atkinson (1775-1833) "The Hut", 1803

“For a child to mock an old man or a cripple, as a rule, flogging will follow. For imitating a drunk, a stutterer or a person with a tic - a very strict debriefing.” l_eriksson collects memories of his mother, her sisters, grandmother and her fellow villagers from a village in the Kostroma region.

About education through labor from an early age:

Everyone knows that the basis for raising children in the Russian village was work. This work was perceived by the child not as a heavy burden, but as a demonstration of his ever-increasing status, approaching adulthood. The reward for this work has always been recognition of the significance of the work done, praise, and demonstration of the results to family, friends, and neighbors. The child did not act as a servant of adults, but as a junior comrade in a common cause. It was unthinkable not to praise him for the work done, to ignore him: apparently, the long experience of generations had inspired people that this was an effective reinforcement of the education of hard work.

Learning new work skills happened patiently, and was done by the one who had time for this, the grandmother, the older children. On the farm in my aunt’s family, I saw children’s tools that were in good working order, carefully made and renewed as they were worn out: in the set of children’s rakes, for example, there were a variety of them - both for a seven-year-old and for a thirteen-year-old child. Among the children's tools there were no dangerous ones - there were no children's scythes. And a shovel with a child's handle - please. Entrusting a child with an impossible or dangerous task was considered a whim.

When learning a particular business, example came first, of course. But they did not spare time for words.

Once the skill was mastered, the activity almost automatically became a responsibility. But the children were not afraid of this, because in the family team everyone knew how to do everything, and there was always someone to back up and replace them.One more thing. The child was shown the place of his help in the system of general affairs, and became familiar with related ones. For example, the collection and cleaning of mushrooms (at first - under the guidance of adults - so as not to miss the poisonous ones) was followed by the science of their preparation. I remember when I was 8 or 9 years old, I was salting collected saffron milk caps in a tiny jar - not only to brag about them later, but also to remember the process.

The more complex and significant the skill the child mastered in the household, the more formal, ritualized signs of respect appeared.- Girls, give Yura a towel, he’s mowing! Pour milk for Yura. Sit down, Yurochka, girls, give Yura some cheesecakes. Teenager Yura himself can perfectly reach everything - but no, he is shown respect, he is carefully served. Sitting next to him, smiling, is his uncle - they don’t dance in front of him like that anymore, he’s an adult, he’s used to it, but Yura needs to be taught and encouraged.

And what a clean porch today! Take off your boots, Yura! (I washed the porch - cleaning the house is for older children, and the canopy and porch are for little ones).

What else? Bringing water (we had no running water) was also a common task. Even the smallest child could carry a liter bucket from the river - it would come in handy. Rinsing clothes, cleaning copper utensils (basins, samovars). Washing dishes at home. Minor cleaning - dust, rugs - adults did not do this. But at the same time, the main tool for forming habits was praise and recognition. As far as I remember, no one yelled at the children about their work duties; this happened for other reasons - pranks, fights, pranks.

Garden. No matter how great the children’s responsibilities in the garden were, there was still an agricultural strategy present. Therefore, the kids usually went there on a specific errand, and the adults gave instructions on when and what to water and weed. The older children could do this without being reminded - they themselves knew what needed to be done. Usually, the garden is the patrimony of grandmothers, who will no longer go to graze, mow, or haul hay. But their experience is enormous - it can be passed on to children. (The traditions of a peasant garden are very different from modern country gardens. If you follow them, there is no “sadism” in gardening; all this plowing over the beds is empty pampering that does not affect the harvest).

Caring for animals had age gradations. Small and not very dangerous animals were trusted to small ones, large and strong ones were trusted only to physically strong and intelligent teenagers. Bees - also with caution, and under the guidance of adults. The children worked mainly with chickens and sheep. (Feeding, penning, collecting chicken eggs, caring for chickens are quite childish things).

But gradually there was also training in handling large cattle. I was forced to milk a cow when I was 10 years old, so I tried it. Aunt stood nearby, prompted, advised.I sat on a horse at 11. No saddle, no bridle - they let me ride, get used to the animal, with the understanding that no one can replace the experience of communication. After several hours of riding (8 kilometers in total), the horse threw me off. They consoled me, but they didn’t particularly pity me. They did not interfere with the process of stuffing cones; they simply kept in mind which cones could be allowed to be filled and which ones could not.

“Girls’ work: introduction to the spinning process. I tried spinning late - at about 9 years old. It was a mess. My grandmother “hidden” my thread into her skein - I saw it and knew: there would be socks that I was involved in.

Small construction, repairs - boys were involved in this. Correct the fence, sharpen the handle for the tool - under the supervision of adults. But the first tool that the boy carved himself was a fishing rod. Fishing is leisure and pleasure. In addition to fishing with a fishing rod, our young relatives were taught how to catch fish with their muzzles and how to install “hooks” (large rods for pike). The kids caught small fish - live bait for pike. The older guys were catching crayfish.

In general, when they laugh at the Chinese, saying that they eat everything that crawls, except a tank, that floats, except a boat, and everything that flies, except an airplane - I want to object - but don’t we? Children in the village were encouraged to collect everything edible. Mom collected “pestas” - the top sprouts of horsetails, fried them in vegetable oil and ate them - they tasted like mushrooms. Sorrel, nettle, gooseberry, many types of berries, a huge list of mushrooms - everything that you can eat, you need to be able to find and cook deliciously. The “School of Survival” worked constantly, and most importantly, it was not divorced from everyday life. Even if there was plenty of “normal” food, a couple of times during the spring one could enjoy “pestles”, and sorrel cabbage soup was cooked, even if there was cabbage. Constantly picking mushrooms and berries in the summer is both children's and old people's fun and work. We were shown how to dry mushrooms and berries, how to make jam, and pickle mushrooms.

But there were things that children were not entrusted with - no matter how you begged. Even the presence of animals and birds during the slaughter was not permitted from an early age. This ban has also been verified over generations. If you allow a child to undergo such processes too early, he will either get scared (treat him later, there are no neurologists in the village!), or he will develop cruelty, which can later result in terrible things. Therefore, everything that was connected with the killing of a living thing was only for older teenagers, and then only in the role of observers, so that they would get used to it.

(By the way, in the Vyatka region, these restrictions were also in effect. I heard that one hunter I know, who involved his first-grader son in skinning killed fur-bearing animals, was condemned by his comrades - they unanimously and justifiably criticized him, and advised him to help in this matter find and hire an adult or handle it yourself).

The result of labor peasant education was the formation of a personality ready for life in any conditions, actually proficient in several specialties at the informal level, and most importantly, not only ready for work, but also unable to imagine life without it. At the same time, the child was socialized and his ability to cooperate with others was developed. Educational methods in this direction, developed over centuries, made it possible to do without violence and, in most cases, even without coercion.

Discuss on the author's blog

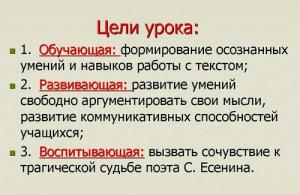

About respect for elders:

F. G. Solntsev. "Peasant family before dinner", 1824

One of the most frequently observed reasons for the use of punitive pedagogy in the peasant environment was the child’s demonstration of disrespect for elders. This was probably one of the biggest sins.

As soon as a parent found out that his child had been rude to an adult, an elderly person, the most severe measures were immediately applied.Moreover, no connection between the behavior of this adult, an old man, and the child’s reaction was taken into account. The old one could have been guilty a hundred times over, unfair, out of his mind - the children had no right to refuse him formal respect.

Even at school, the most absurd teacher could count on the support of his parents in any of his demands. Another thing is that I don’t remember a case when a dull student at home was scolded for failing him if he was hardworking and dexterous in his daily work. The parents patiently endured the teacher’s reproaches, but did not fall into any kind of sadness because of this and did not torment the child.It was possible to stand up for a child in front of another adult only in the form of dialogue - in persuasion, explanations. But only to a certain limit, usually relating to assault.

No matter how much was said among the Russian peasantry about forgiveness and the harm of vindictiveness, these words did not always serve as a guide to action. The hidden resentment smoldered for years, and very often found a way out, and a merciless way out - at a convenient time. The Russian peasant eats the dish of revenge not cold, but completely icy! But whoever provides the ingredients for this dish can be sure that it is waiting in the wings.

Events to which I sometimes observed reactions occurred 30-40, or even 50 years before the response to them. You can say that this is bad, but it is so, and this must be kept in mind.

Older teenagers are often introduced to family grievances, and willingly take over the baton of relationships with a particular person or family. At the same time, there were also conversations with them about the fact that “we must forgive.” But always, under the influence of opposing suggestions, the one that was made with greater passion and fell on the basis of a greater personal predisposition happens to prevail.

It manifested itself, for example, like this. The child committed some kind of trick against a neighbor. Shaked the apple tree in his garden. Formally, he will always be reprimanded. But if he heard a hundred times from his parents what a bastard he, this neighbor, is, he will feel like water off a duck’s back, even if they take him by the collar to this neighbor and force him to apologize.By the way, for just as long, from generation to generation, gratitude for good, especially done in some extraordinary, important and difficult circumstances, has been passed on. Helping a widow and supporting an orphan is not only a charitable deed. The orphan will grow up and at the most unexpected moment will repay kindness for kindness. Children and grandchildren are taught to honor the benefactor and his family.

Tolerance

As a rule, a child's mockery of an old or crippled person will result in a flogging.

For imitating a drunk, a stutterer or a person with a tic - a very strict debriefing, verbose, with examples, menacing, but without violence.

Open ridicule of a foreigner, if detected, will be condemned, but gently, in the form of admonitions. If they were rude, and their target is adult, elderly or helpless, a thrashing is coming.

If this is a child of the same age, the parents will remain indifferent “until first blood.” You can't attach words to action. In the event of a fight due to “national hatred” without a clear reason, parents can punish the child, and most often they will do this, keeping in mind the rules of behavior towards any person.Children's conflicts

The main rule: “Toys are not roars.”

Some parents refuse to listen to complaints, but this is an individual trait, not a tradition. Most often, such deafness is characteristic of incomplete, unhappy, poor families - in short, families with a defect.In general, any mention of the fact that in peasant families there were no conversations with children is an absolutization of particulars, distortions, and human damage. They did, and a lot. Firstly, families in villages have always been large and branched, with several generations living in them - it would be convenient for someone to listen to a child’s complaint or answer his question. Judging by the stories of my mother and her sisters, these conversations, conversations, suggestions were more than they would like. This was the only thing the old people did, for example. Sometimes, for patiently listening to instructions, the child was even given encouragement - a nut, candy, a pie, that is, adults understood that it was sometimes not easy to listen to them.

The structure of peasant work also involves both very busy periods - from dawn to dusk, and pauses, even associated with the same seasons and weather conditions. There were no opportunities for isolation either - “our own rooms,” etc., except perhaps the corner behind the old man’s stove, so that he would not be disturbed by noise and fuss. Sometimes other people's children might wander in to listen to the conversations - but no one spared this goodness - a tongue without bones!Dismantling a child’s conflict or a child’s conflict with an adult is an entertainment and an educational moment; parents did not shy away from this, and only in cases of incredible busyness in the suffering or personal unhealthy unsociability on the verge of sociopathy did they shy away from this task.

One of these “information sources” for pedagogical conversations was often epics, stories, tales and even gossip. The parent expressed his attitude to a particular event or behavior, and the child listened and wondered.

Lesser gods

With these words, I decided to designate the role of his father and mother for a peasant child. Respect for parents was absolute, but to be honest, I didn’t see how it was inculcated? This is, perhaps, one of the mysteries of traditional upbringing - its basis is the unquestioned authority of elders.

I came across only evidence, and not the formation of this phenomenon. A parent does not have to be strong, honest, smart, successful, fair, kind, sober - it is enough for him to simply be. Violence could not be the basis for this. I have seen situations where a parent was so weak, insignificant and pathetic that even his own child would not be afraid of him. But love and outward respect were always demonstrated. It was possible to “abandon” my parents only with their blessing - to go to foreign lands to seek happiness. As a rule, all those who left experienced agony and “withdrawal” for a long time.With such a basis for the relationship between parents and children, a very diverse and effective arsenal of pedagogical influences was in the hands of parents. This made cruelty unnecessary and even undesirable. If it is enough for the father or mother to frown for the child to realize that he has acted badly, there is no need to flog him like Sidorov’s goat. In most of the peasant families I knew, children were not spanked, much less flogged. And they didn’t scold me. They were simply sometimes reproached, and they immediately rushed headlong to correct mistakes, so as not to upset mom and dad. Parental praise, smiles, and stingy affection also meant a lot to children.

By the way, I talked a lot with the generation who called their father “dad”, “dad” - this came from seminarians who studied Latin. (They didn’t hear about French and the French in the village of F. - the master was from the Baltic Germans, a baron, and with foreigners besides him it was difficult: nearby, in more or less populated places, Ivan Susanin took someone somewhere. And in the village of F .there were practically no brunettes).I have seen examples of children’s devotion and faith in their parents that make the same samurai legends about stalwart ronins fade.

This, and not religion or labor on the land, in my opinion, was the basis of Russian peasant education. When this pillar began to shake, the whole structure went at random.

But I’ll tell you about her other features later.

Peasant meal

The everyday peasant table did not have much variety. Black bread, cabbage soup, porridge and kvass - that’s probably all the pickles. Of course, forest gifts were a serious help - mushrooms, berries, nuts, honey. But the basis of everything has always been bread.

"The barn is the head of everything"

There are so many folk sayings, proverbs and sayings about him: “Bread is the head of everything”, “Bread and water is peasant food”, “Bread on the table - and the table is a throne, but not a piece of bread - and the table is a board”, “Hood lunch if there is no bread."

“Bread and salt” greeted dear guests, invited them to the table, wished them well-being, and greeted the newlyweds on their wedding day. Not a single meal was complete without bread. Cutting bread at the table was considered an honorable duty of the head of the family.

Bread also served as ritual food. Prosphoras were baked from sour dough, intended for the Christian sacrament of communion. A special type of bread - perepecha - took part in wedding ceremony. At Easter they baked Easter cakes, at Maslenitsa they said goodbye to the winter with pancakes, and they greeted spring with “larks” - gingerbread cookies shaped like birds.

The peasant could not imagine life without bread. In lean years, famine began, despite the fact that there was plenty of animal food.

They usually baked bread once a week. This is a complex and time-consuming matter. In the evening, the housewife prepared the dough in a special wooden tub. The dough and the tub were called the same thing - kvashnya. The tub was constantly in use, so it was rarely washed. A lot of sarcastic jokes are associated with this. They said that one day the cook lost the frying pan on which she usually baked pancakes. I couldn’t find it for a whole year and only discovered it when I started washing the kneading bowl.

Before putting the dough, the walls of the kneading bowl were rubbed with salt, then filled with warm water. To make sourdough, throw in a piece of dough left over from previous baking and add flour. After mixing everything well, leave it overnight in a warm place. By morning the dough had risen, and the cook began to knead it. This difficult work continued until the dough began to lag behind the hands and the walls of the tub. The kneading bowl was again placed in a warm place for a while, and then kneaded again. Finally the dough is ready! All that remains is to divide it into large, smooth loaves and place them in the oven on a wooden shovel. After some time, the hut was filled with the incomparable smell of baking bread.

How to check if the loaf is ready? The hostess took it out of the oven and tapped it on the bottom. Well-baked bread rang like a tambourine. A woman who knew how to bake delicious bread was especially respected in the family.

The baked bread was stored in special wooden bread bins. They also served it on the table. These bread boxes were treasured and even given to daughters as dowries.

In the village they baked mostly black, rye bread. White wheat kalach was a rare guest on the peasant table; it was considered a delicacy that was allowed only on holidays. Therefore, if a guest could not even be “lured with a roll,” the offense was serious.

In hungry, lean years, when there was not enough bread, quinoa, tree bark, ground acorns, nettles, and bran were added to the flour. The words about the bitter taste of peasant bread had a direct meaning.

Not only bread was baked from flour. Russian cuisine is rich in flour dishes: pies, pancakes, pancakes, gingerbreads were always served on the festive peasant table.

Pancakes are perhaps the most popular Russian dish. Known since pagan times, they symbolized the sun. In the old days, pancakes as a ritual food were an integral part of many rituals - from birth (a woman in labor was fed a pancake) to death (pancakes with kutia were used to commemorate the deceased). And, of course, what would Maslenitsa be without pancakes? However, truly Russian pancakes are not the ones that every housewife bakes today from wheat flour. In the old days, pancakes were baked only from buckwheat flour.

They were more loose, fluffy, with a sour taste.

Not a single peasant holiday in Rus' was complete without pies. The word “pie” itself is believed to come from the word “feast” and originally meant festive bread. Pies are still considered a decoration for the festive table: “The hut is red in its corners, and lunch is in pies.” Housewives have baked so many pies since ancient times! In the seventeenth century. at least 50 types of them were known: yeast, unleavened, puff pastry - from different types of dough; hearth, baked on a hearth without oil, and yarn, baked in oil. Pies were baked in different sizes and shapes: small and large, round and square, elongated and triangular, open (rasstegai) and closed. And there were so many different fillings for pies: meat, fish, cottage cheese, vegetables, eggs, cereals, fruits, berries, mushrooms, raisins, poppy seeds, peas. Each pie was served with a specific dish: a pie with buckwheat porridge was served with fresh cabbage soup, and a pie with salted fish was served with sour cabbage soup. Pie with carrots goes with the fish soup, and with meat goes with the noodles.

Gingerbread cookies were an indispensable decoration of the festive table. Unlike pies, they did not have a filling, but honey and spices were added to the dough - hence their name “gingerbread”. The gingerbread cookies were shaped like some kind of animal, fish, or bird. By the way, Kolobok, a character from a famous Russian fairy tale, is also a gingerbread, only spherical. Its name comes from the ancient word “kola” - circle. At Russian weddings, when the celebration was coming to an end, small “disperse” gingerbread cookies were distributed to the guests, transparently hinting that it was time to go home.

“Shchi and porridge are our food”

That's what people liked to say. Porridge was the simplest, most satisfying and affordable food. A little cereal or grain, water or milk, salt to taste - that’s the whole secret.

In the 16th century At least 20 types of porridges were known - as many cereals as there were porridges. And different types of grain grinding made it possible to prepare special porridge. IN Ancient Rus' porridge was any stew made from chopped products, including fish, vegetables, and peas.

Just like without pancakes, not a single ritual was complete without porridge. They cooked it for weddings, christenings, and funerals. According to custom, the newlyweds were fed porridge after their first wedding night. Even kings followed this tradition. A wedding feast in Rus' was called “porridge”. Preparations for this celebration were very troublesome, which is why they said about the young people: “they made a mess.” If the wedding was upset, then the guilty were condemned: “you can’t cook porridge with them.”

A type of porridge is funeral kutia, mentioned in The Tale of Bygone Years. In ancient times, it was prepared from wheat grains and honey.

Many ancient peasant porridges - buckwheat, millet, oatmeal - are still on our table to this day. But many people know about spelled only from Pushkin’s fairy tale about the worker Balda, who was fed spelled by a greedy priest. This was the name of the cereal plant - something between wheat and barley. Spelled porridge, although nutritious, tastes rough, which is why it was the food of the poor. Pushkin gave his priest the nickname “fat forehead.” Oatmeal was a specially prepared oatmeal that was also used to make porridge.

Some researchers consider porridge to be the mother of bread. According to legend, an ancient cook, while preparing porridge, overloaded the grain and ended up with a flatbread.

Shchi is another native Russian food. True, in the old days almost all stews were called cabbage soup, and not just modern cabbage soup. The ability to cook delicious cabbage soup, as well as bake bread, was a mandatory quality of a good housewife. “Not the housewife who speaks beautifully, but the one who cooks cabbage soup well!” In the 16th century one could taste “shti cabbage”, “shti borschov”, “shti repyany”.

Since then, a lot has changed in the diet. Previously unknown potatoes and tomatoes have firmly established themselves on our table. Many vegetables, on the contrary, have almost disappeared: for example, turnips. But in ancient times it was as common as cabbage. Turnip stew never left the peasant table, and before the advent of potatoes it itself was considered “second bread” in Russia. They even made kvass from turnips.

Traditional Russian cabbage soup was cooked from fresh or sour cabbage in meat broth. In the spring, instead of cabbage, the housewife seasoned the cabbage soup with young nettles or sorrel.

The famous French novelist Alexandre Dumas admired Russian cabbage soup. He returned from Russia with their recipe and included it in his cookbook. By the way, cabbage soup itself could be brought to Paris from Russia. Russian memoirist of the 18th century. Andrei Bolotov tells how in winter travelers took a whole tub of frozen cabbage soup with them on a long journey. At postal stations, they were warmed up and eaten as needed. So, perhaps, Mr. Khlestakov was not lying so much when he talked about “soup in a saucepan... straight from Paris.”

Peasant cabbage soup did not always contain meat. They used to say about these: “At least you can whip cabbage soup.” But the presence of meat in cabbage soup was determined not only by the wealth of the family. Religious traditions meant a lot. All days of the year were divided into fast days, when you could eat everything, and fast days - without meat and dairy products. Wednesdays and Fridays were fast all year round. In addition, long fasts, from two to eight weeks, were observed: the Great, Petrov, Uspensky, etc. There were about two hundred fasting days a year.

When talking about peasant food, one cannot help but recall once again the Russian oven. Anyone who has tried bread, porridge or cabbage soup cooked in it at least once in their life will not forget their amazing taste and aroma. The secret is that the heat in the oven is distributed evenly and the temperature remains constant for a long time. Dishes containing food do not come into contact with fire. In round, pot-bellied pots, the contents are heated from all sides without burning.

Casanova drink

The favorite drink in Rus' was kvass. But its value was not limited only to taste. Kvass and sauerkraut were the only means of salvation from scurvy during the long Russian winters, when food was extremely scarce. Even in ancient times, kvass was credited with medicinal properties.

Each housewife had her own recipe for making a variety of kvass: honey, pear, cherry, cranberry, apple - it’s impossible to list them all. Some good kvass competed with some “drunk” drinks - beer, for example. Famous adventurer of the 18th century. Casanova, who traveled halfway around the world, visited Russia and spoke with delight about the taste of kvass.

“Eat cabbage soup with meat, but if not, it’s bread with kvass,” advised a Russian proverb. Kvass was available to anyone. Many dishes were prepared on its basis - okroshka, botvinya, beetroot soup, tyuryu). Botvinya, for example, well known in Pushkin’s time, is almost forgotten today. It was made from kvass and boiled tops of some plants - beets, for example, hence the name - “botvinya”. Prison was considered the food of the poor - pieces of bread in kvass were sometimes their main food.

Kissel is as ancient a drink as kvass. There is an interesting entry about jelly in the Tale of Bygone Years. In 997, the Pechenegs besieged Belgorod. The siege dragged on, and famine began in the city. The besieged were already ready to surrender to the mercy of the enemy, but one wise old man advised them how to escape. The townspeople collected by the handful all the remaining oats, wheat, and bran. They made a mash out of them, from which they make jelly, poured it into a tub and put it in the well. A tub of honey was placed in another well. Pechenezh ambassadors were invited to negotiations and treated to jelly and honey from wells. The Pechenegs then realized that it was pointless to continue the siege, and lifted it.

Beer was also a common drink in Rus'. A detailed recipe for its preparation can be found, for example, in Domostroy. At the turn of the 16th–17th centuries. beer was even part of feudal taxes.

Customs of the peasant table

It is difficult to say exactly how many times a day peasants ate in the 16th or 17th centuries. "Domostroy" talks about two obligatory meals - lunch and dinner. They didn’t always have breakfast: people believed that the day’s food had to be earned first. In any case, there was no breakfast common to all family members. Got up in different times and immediately got to work, perhaps grabbing some of the leftovers from yesterday's food. The whole family gathered at the dinner table at noon.

The peasant knew the price of a piece of bread from childhood, so he treated food sacredly. Meal in peasant family resembled a sacred ceremony. The first to sit down at the table, in the red corner under the icons, was the father, the head of the family. Other family members also had strictly established places depending on age and gender.

Before eating, they always washed their hands, and the meal began with a short prayer of thanks, which was said by the owner of the house. In front of each meal on the table there was a spoon and a piece of bread, which in some ways replaced a plate. The food was served by the hostess - the mother of the family or daughter-in-law. In a large family, the hostess had no time to sit down at the table during dinner, and she ate alone when everyone was fed. There was even a belief that if the cook stood at the stove hungry, dinner would taste better.

Each person scooped liquid food from a large wooden bowl, one for everyone, with his own spoon. The owner of the house vigilantly monitored compliance with the rules of behavior at the table. Eating was supposed to be done slowly, without overtaking each other. It was impossible to eat “sip,” that is, scoop up the stew twice without taking a bite of the bread. The thickets, pieces of meat and lard at the bottom of the bowl were divided after the slurry was eaten, and the right to choose the first piece belonged to the head of the family. You were not supposed to take two pieces of meat with a spoon at once. If one of the family members absent-mindedly or intentionally violated these rules, then as punishment he would immediately receive a blow to the forehead with the master’s spoon. In addition, it was forbidden to talk loudly at the table, laugh, knock on the dishes with a spoon, throw leftover food on the floor, or get up without finishing the meal.

The family did not always gather for dinner at the house. During the lean season, they ate right in the field so as not to waste valuable time.

On holidays, villages often held “brotherhood” feasts by sharing. They chose the organizer of the brotherhood - the headman. He collected their share from the feast participants, and sometimes served as a toastmaster at the table. The whole world brewed beer, cooked food, and set the table. At fraternities there was a custom: those gathered passed a bowl of beer or honey around - a bro. Everyone took a sip and passed it to their neighbor. Those gathered had fun: they sang, danced, and played games.

Hospitality has always been a characteristic feature of Russians. It was appreciated primarily by its hospitality. The guest was supposed to be given water and food to his fill. “Everything that is in the oven is on the table,” a Russian proverb teaches. Custom dictated almost forcefully feeding and drinking a guest, even if he was already full. The owners knelt down and tearfully begged them to eat and drink just a little more.

The peasants ate to their fill only on holidays. Low yields, frequent crop shortages, and heavy feudal duties forced people to deny themselves the most necessary things—food. Maybe this explains national trait Russians - a love for a magnificent feast, which has always surprised foreigners.

The spiritual and moral traditions of the Smolensk peasants developed in the general mainstream of the spiritual traditions of the peasantry of the Great Russian provinces. However, a feature of the Smolensk province was its location on the western outskirts historical Rus'. Based on population, the province was divided into counties with a predominance of the Great Russian tribe - 4 eastern counties and Belsky county, and counties with a predominance of the Belarusian tribe. The traditions of the peasants of the Great Russian districts of the Smolensk province differed in many ways from the traditions of the peasants of the Belarusian districts. This manifested itself both in home life and in folk costume, in folk superstitions, fairy tales, songs. Historically, the western part of the Smolensk province experienced greater influence from Poland and the Principality of Lithuania, the eastern part - greater influence from the Moscow Principality.

The traditions and customs of Smolensk peasants were closely connected with Christianity and church traditions. “A good beginning,” writes Y. Solovyov, “is revealed in piety, which seems to be stronger in the Great Russian districts than in the Belarusian ones,”112 but due to the lack of enlightenment, the Christian faith and tradition were perceived by the villagers in a distorted form. Often this was mixed with superstition, speculation, fears, and incorrect conclusions that arose as a result of a lack of basic knowledge. The tradition, which developed over centuries, was passed down from generation to generation only through oral instruction, for the reason that most peasants were illiterate, which in turn prevented the penetration of information from the outside (non-peasant) world. Thus, informational isolation was mixed with class isolation. The lack of schools in the village was an excellent breeding ground for all kinds of superstitions and false knowledge to flourish. The lack of an education and enlightenment system in the countryside was the main reason for the backwardness of peasants compared to city residents.

Before the abolition of serfdom, the role of the state in the education and enlightenment of peasants was negligible, and this task was primarily assigned to the Church everywhere and to landowners in privately owned villages. But very often landowners did not see the need for cultural development their peasants, for the most part the peasants were considered by the landowners as a source of wealth and prosperity, and did not care about the general cultural level of their “baptized property.” The Church, as a structure subordinate to the state, was entirely dependent on the decisions of the Synod in this matter, and any improvements in the matter of training and enlightening the peasants were the private initiatives of one or another priest. Nevertheless, it is necessary to note that the church remained, both before and after the abolition of serfdom, the only “cultural center” in the village.

Gradually, the situation in public education begins to change. After the abolition of serfdom in the Smolensk province, schools were opened in many places to educate peasant children. On the initiative of the zemstvo, at peasant gatherings, decisions were often made to raise funds for the maintenance of schools in the amount of 5-20 kopecks per per capita plot.

In 1875, the zemstvo allocated up to 40 thousand rubles for the maintenance of gymnasiums, “ educational institutions, almost beyond the reach of children of the peasant class" (GASO, f. kans. smol. governor (f1), op. 5, 1876, d. 262, l. 77-78) Sometimes schools were opened on the initiative of the peasants themselves, at their expense . Some of the literate fellow villagers undertook to teach the children of their own, and sometimes even a neighboring village, for this the “teacher” received small (no more than 50 kopecks per student per school year, which could last no more than 3-4 months) money and food, and if the “teacher” was not local, then the peasants also provided a hut for the school. Often such a “school” moved from one hut to another. In a lean year, the number of students and the number of schools declined sharply. We can say that after the abolition of serfdom, the situation in the education of peasants changed a little in better side. IN rural schools taught children reading, writing and the four rules of arithmetic, and in many schools - only reading. Interesting are the observations of A.N. Engelgardt113 that peasants who go to work in the cities are more willing to teach their children to read and write. This is, of course, due to the fact that people who saw the fruits of education in the cities better understood that a literate person had more prospects in life and, apparently, less than other peasants connected the future of their children with the village.

Not in the best possible way This was also the case with regard to medical care. There was virtually no medical care for the rural population. For 10 thousand population of the Smolensk province at the beginning of the 20th century. there were 1 doctor, 1.3 paramedics and per 10 thousand female population - 1.4 midwives. (statistical yearbook of Russia. 1914) It is not surprising that various epidemics were raging then, about which now the population is completely unaware. Outbreaks of smallpox, cholera, and various typhus recurred periodically. The mortality rate was also high, especially among children. A.P. Ternovsky calculated on the basis of the books of the church parish that from 1815 to 1886, 3923 people died in Mstislavskaya Slobodka, including children under one year old - 1465, or 37.4%, aged 1 - 5 years - 736, or 19.3%. Thus, children under 5 years of age account for 56.7% of all deaths. “Very often,” writes Engelhardt, “good food, a warm room, getting rid of work would be the most the best remedy for healing."

Peasant morality, formed over the centuries, was closely connected with agricultural labor, as a result of which one of the most important moral guidelines was hard work. “To run a household, don’t shake your trousers; to run a household, don’t walk around open-mouthed,” say popular sayings. According to the peasant’s conviction, only a hardworking person, a good owner, could be a good, correct person.

“Industriousness was highly valued by the public opinion of the village.” Even the family was considered by the peasants, first of all, as a labor unit, as a labor collective bound by mutual obligations, where everyone was a worker. “The marital union was the basis of the material well-being of the economy...Marriage for the peasants was necessary from an economic point of view.” For this reason, newborn boys were seen as more valuable workers compared to girls. Here it is necessary to remember the traditions associated with family and marriage.

Matchmaking or conspiracy was the conclusion of a preliminary agreement between the families of the future bride and groom. At the same time, “the choice of the bride was the lot of the parents... the groom’s opinion was rarely asked, personal sympathies were not of decisive importance, and marriage was, first of all, a business transaction.” This is also confirmed by the Russian historian S.V. Kuznetsov: “The main motivation when entering into a marriage is the desire to enslave a free worker, but recently love marriages have become more common. When choosing a bride, good health, ability to work, and modesty are especially valued; in addition, they take into account what kind of relatives the bride has. When choosing a groom, it is most valued if the groom is the only son of the parents.”119 The bride’s parents were obliged to give a dowry for their daughter, which was the parents’ contribution to the economy of the new family. The dowry consisted of money and property. The monetary part became the property of the husband, while the property part (household items) became either joint property or the property of the wife and was then inherited by the daughters. In general, it should be noted that family life, and in general, relations between peasants were regulated by customary law - a law that had developed over centuries, passed on from generation to generation and which, according to the deep conviction of the peasants, was the only correct one. Based on the principles of customary law, the responsibilities of wife and husband within the family were divided. The husband did not interfere in the sphere of a woman's duties, the wife should not interfere in the sphere of her husband's duties. If these immutable rules were violated, the husband was obliged to restore order by any means possible - customary law allowed the head of the family to resort to violence and beatings in this case, this was considered a manifestation of love.

Another important moral ideal among the peasants was collectivism - the priority of the public over the personal. The principle of conciliarity ( general solution) was one of the basic principles of house building among peasants. Only the decision that was made jointly was, in the deep conviction of the peasants, correct and worthy of adoption.

The economic, social and family life of the Russian village was led by the land community. Its main purpose was to maintain justice in the use of land: arable land, forests, meadows. From here stemmed the principles of conciliarity, collectivism, and the priority of the public over the personal. In a system where one of the main values was the priority of the public over the personal, where the most important thing was the decision (even if incorrect) of the majority, in such a system, naturally, the role of individual actions and personal initiative was negligible and neglected. If personal initiative was welcomed, it was only if it brought general benefit to the entire “world.”

It is necessary to note the special role of public opinion in the life of the Russian village. Public opinion (the opinion of rural society) was an important factor in assessing certain actions of community members. All actions were viewed through the prism of public benefit, and only socially beneficial acts were considered as good. “Beyond the family, public opinion was no less significant, exerting a lasting influence on children and adults.”

As a result of the reforms of the 60-70s, the value system of the peasantry experienced serious changes. A tendency to shift the value orientation from public to personal is beginning to develop. The development of market relations influenced both the forms of activity and the consciousness of the traditional peasantry. Along with the emergence of other sources of information about the world around us besides parents, the views younger generation began to differ from the views of their elders, and conditions arise for the emergence of new values. The penetration of new views and ideas into the countryside in the post-reform period was most facilitated by: 1) the departure of peasants to the cities to earn money; 2) military service; 3) penetration of urban culture into rural life through the press and other sources of information. But the most important factor in changes in peasant consciousness, nevertheless, was non-agricultural waste. Peasant youth spent a long time in large industrial cities and absorbed urban culture and new traditions. They brought all this with them upon returning to the village. New traditions covered all spheres of rural life, from costume and dance to religious views. Along with other changes in traditional rural consciousness, the view of human personality is changing. This view is expressed in the idea that a person can exist outside the community as a separate person with his own individual needs and desires. In the 70s, the number of family divisions began to increase. A large patriarchal family, in which several generations of relatives lived under one roof, is gradually turning into a small family consisting of a husband, wife and young children. This process intensified in the last quarter of the 19th century. At the same time, the view of a woman within a small family is changing, her economic importance and the degree of influence on resolving family issues are increasing. This process contributed to the gradual increase in the personal freedom of the peasant woman, the expansion of her rights, incl. property rights. With the growing influence of urban culture on peasant ideas and the active spread of the small family, the increasing importance of women in the household, a humanization of family relationships was observed.

At this time, a fusion of urban (more secular) culture and rural culture takes place. The traditions of the village are gradually being replaced by the traditions of the city. As the rural population leaves for the cities, a change occurs in the spiritual traditions of the peasants. The changes that occurred during the period of great reforms entailed irreversible processes in traditional way of life rural life, in spiritual traditions and relationships within the rural community. Along with liberation from serfdom, urban culture begins to penetrate into the village - this process takes place gradually and slowly, but its effect becomes irreversible. The villager looked at the city dweller as a more educated and mentally developed person, as a bearer of a higher culture, and most of all this view was instilled among young people. The process of property stratification among the peasantry only accelerated the destruction of peasant traditions and the penetration of urban culture into the countryside. It should be noted that the life of a city dweller was private - he was guided in making daily decisions only by his views and beliefs, while the life of a peasant was communal - a village resident was entirely dependent on the community and its opinions, personal initiative was under the constant control of the community . Along with the end of the isolation of the village from the city and urban traditions, the process of changing traditions within the rural community begins. This is manifested in the attitude of young people to the church and church tradition, and in the increasing number of family divisions, and in less significant manifestations, such as wearing urban clothing (cap, boots) and borrowing urban songs and dances.

A Russian dwelling is not a separate house, but a fenced yard in which several buildings, both residential and commercial, were built. Izba was the general name for a residential building. The word "izba" comes from the ancient "istba", "heater". Initially, this was the name given to the main heated living part of the house with a stove.

As a rule, the dwellings of rich and poor peasants in villages practically differed in the quality and number of buildings, the quality of decoration, but they consisted of the same elements. Availability of such outbuildings, such as a barn, barn, barn, bathhouse, cellar, stable, exit, moss barn, etc., depended on the level of development of the economy. All buildings were literally chopped with an ax from the beginning to the end of construction, although longitudinal and transverse saws were known and used. The concept of “peasant yard” included not only buildings, but also the plot of land on which they were located, including a vegetable garden, orchard, threshing floor, etc.

Main building material there was a tree. The number of forests with excellent “business” forests far exceeded what is now preserved in the vicinity of Saitovka. Pine and spruce were considered the best types of wood for buildings, but pine was always given preference. Oak was valued for its strength, but it was heavy and difficult to work with. It was used only in the lower crowns of log houses, for the construction of cellars, or in structures where special strength was needed (mills, wells, salt barns). Other tree species, especially deciduous (birch, alder, aspen), were used in construction, usually of outbuildings

For each need, trees were selected according to special characteristics. So, for the walls of the log house, they tried to select special “warm” trees, covered with moss, straight, but not necessarily straight-layered. At the same time, not just straight, but straight-layered trees were necessarily chosen for roofing. More often, log houses were assembled in the yard or close to the yard. We carefully chose the location for our future home.

For the construction of even the largest log-type buildings, a special foundation was usually not built along the perimeter of the walls, but supports were laid in the corners of the huts - large boulders or so-called “chairs” made of oak stumps. In rare cases, if the length of the walls was much greater than usual, supports were placed in the middle of such walls. The very nature of the log structure of the buildings allowed us to limit ourselves to support on four main points, since the log house was a seamless structure.

The vast majority of buildings were based on a “cage”, a “crown” - a bunch of four logs, the ends of which were chopped into a connection. The methods of such cutting could vary in technique.

The main structural types of log-built peasant residential buildings were “cross”, “five-walled”, and a house with a log. For insulation, moss mixed with tow was laid between the crowns of the logs.

but the purpose of the connection was always the same - to fasten the logs together into a square with strong knots without any additional joining elements (staples, nails, wooden pins or knitting needles, etc.). Each log had a strictly defined place in the structure. Having cut down the first crown, a second was cut on it, a third on the second, etc., until the frame reached a predetermined height.

The roofs of the huts were mainly covered with thatch, which, especially in lean years, often served as feed for livestock. Sometimes wealthier peasants erected roofs made of planks or shingles. The tes were made by hand. To do this, two workers used tall sawhorses and a long rip saw.

Everywhere, like all Russians, the peasants of Saitovka, according to a widespread custom, when laying the foundation of a house, placed money under the lower crown in all corners, with the red corner receiving a larger coin. And where the stove was placed, they did not put anything, since this corner, according to popular belief, was intended for the brownie.

In the upper part of the log house across the hut there was a matka - a tetrahedral wooden beam that served as a support for the ceilings. The matka was cut into the upper crowns of the log house and was often used to hang objects from the ceiling. So, a ring was nailed to it, through which the ochep (flexible pole) of the cradle (shaky pole) passed. In the middle, to illuminate the hut, a lantern with a candle was hung, and later - a kerosene lamp with a lampshade.

In the ceremonies associated with the completion of the construction of a house, there was a mandatory treat, which was called “matika”. In addition, the laying of the womb itself, after which a fairly large amount of construction work still remained, was considered as a special stage in the construction of the house and was furnished with its own rituals.

In the wedding ceremony, for a successful matchmaking, the matchmakers never entered the house for the queen without a special invitation from the owners of the house. In the popular language, the expression “to sit under the womb” meant “to be a matchmaker.” The womb was associated with the idea of the father's house, good luck, and happiness. So, when leaving home, you had to hold on to your uterus.

For insulation along the entire perimeter, the lower crowns of the hut were covered with earth, forming a pile in front of which a bench was installed. In the summer, old people whiled away the evening time on the rubble and on the bench. Fallen leaves and dry soil were usually placed on top of the ceiling. The space between the ceiling and the roof - the attic - in Saitovka was also called the stavka. It was usually used to store things that had outlived their useful life, utensils, dishes, furniture, brooms, tufts of grass, etc. The children made their own simple hiding places on it.

A porch and a canopy were always attached to a residential hut - a small room that protected the hut from the cold. The role of the canopy was varied. This included a protective vestibule in front of the entrance, additional living space in the summer, and a utility room where part of the food supplies were kept.

The soul of the whole house was the stove. It should be noted that the so-called “Russian”, or more correctly oven, is a purely local invention and quite ancient. It traces its history back to Trypillian dwellings. But during the second millennium AD, very significant changes occurred in the design of the oven itself, which made it possible to use fuel much more fully.

Building a good stove is not an easy task. First, a small wooden frame (opechek) was installed directly on the ground, which served as the foundation of the furnace. Small logs split in half were laid on it and the bottom of the oven was laid on them - under, level, without tilting, otherwise the baked bread would turn out lopsided. A furnace vault was built above the hearth from stone and clay. The side of the oven had several shallow holes, called stoves, in which mittens, mittens, socks, etc. were dried. In the old days, huts (smoking houses) were heated in a black way - the stove did not have a chimney. The smoke escaped through a small fiberglass window. Although the walls and ceiling became sooty, we had to put up with it: a stove without a chimney was cheaper to build and required less firewood. Subsequently, in accordance with the rules of rural improvement, mandatory for state peasants, chimneys began to be installed above the huts.

First of all, the “big woman” stood up - the owner’s wife, if she was not yet old, or one of the daughters-in-law. She flooded the stove, opened the door and smoker wide. The smoke and cold lifted everyone. The little kids were sat on a pole to warm themselves. Acrid smoke filled the entire hut, crawled upward, and hung under the ceiling taller than a man. An ancient Russian proverb, known since the 13th century, says: “Having not endured smoky sorrows, we have not seen warmth.” The smoked logs of the houses were less susceptible to rotting, so the smoking huts were more durable.

The stove occupied almost a quarter of the home's area. It was heated for several hours, but once warmed up, it kept warm and warmed the room for 24 hours. The stove served not only for heating and cooking, but also as a bed. Bread and pies were baked in the oven, porridge and cabbage soup were cooked, meat and vegetables were stewed. In addition, mushrooms, berries, grain, and malt were also dried in it. They often took steam in the oven that replaced the bathhouse.

In all cases of life, the stove came to the aid of the peasant. And the stove had to be heated not only in winter, but throughout the year. Even in summer, it was necessary to heat the oven well at least once a week in order to bake a sufficient supply of bread. Using the ability of the oven to accumulate heat, peasants cooked food once a day, in the morning, left the food inside the oven until lunch - and the food remained hot. Only during late summer dinners did food have to be heated. This feature of the oven had a decisive influence on Russian cooking, in which the processes of simmering, boiling, and stewing predominate, and not only peasant cooking, since the lifestyle of many small nobles was not very different from peasant life.

The oven served as a lair for the whole family. Old people slept on the stove, the warmest place in the hut, and climbed up there using steps - a device in the form of 2-3 steps. One of the obligatory elements of the interior was the floor - a wooden flooring from the side wall of the stove to the opposite side of the hut. They slept on the floorboards, climbed out of the stove, and dried flax, hemp, and splinters. Bedding and unnecessary clothes were thrown there for the day. The floors were made high, at the same level as the height of the stove. The free edge of the floors was often protected by low railings-balusters so that nothing would fall from the floors. Polati were a favorite place for children: both as a place to sleep and as the most convenient observation point during peasant holidays and weddings.

The location of the stove determined the layout of the entire living room. Usually the stove was placed in the corner to the right or left of the front door. The corner opposite the mouth of the stove was the housewife's workplace. Everything here was adapted for cooking. At the stove there was a poker, a grip, a broom, and a wooden shovel. Nearby there is a mortar with a pestle, hand millstones and a tub for leavening dough. They used a poker to remove the ash from the stove. The cook grabbed pot-bellied clay or cast iron pots (cast iron) with her grip and sent them into the heat. She pounded the grain in a mortar, clearing it of husks, and with the help of a mill she ground it into flour. A broom and a shovel were necessary for baking bread: a peasant woman used a broom to sweep under the stove, and with a shovel she planted the future loaf on it.

There was always a cleaning bowl hanging next to the stove, i.e. towel and washbasin. Underneath there was a wooden basin for dirty water. In the stove corner there was also a ship's bench (vessel) or counter with shelves inside, used as a kitchen table. On the walls there were observers - cabinets, shelves for simple tableware: pots, ladles, cups, bowls, spoons. The owner of the house himself made them from wood. In the kitchen one could often see pottery in “clothes” made of birch bark - thrifty owners did not throw away cracked pots, pots, bowls, but braided them with strips of birch bark for strength. Above there was a stove beam (pole), on which kitchen utensils were placed and various household supplies were placed. The eldest woman in the house was the sovereign mistress of the stove corner.

The stove corner was considered a dirty place, in contrast to the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always sought to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz or colored homespun, a tall cabinet or a wooden partition. The corner of the stove, thus closed, formed a small room called a “closet”. The stove corner was considered an exclusively female space in the hut. During the holiday, when many guests gathered in the house, a second table was placed near the stove for women, where they feasted separately from the men sitting at the table in the red corner. Men, even their own families, could not enter the women’s quarters unless absolutely necessary. The appearance of a stranger there was considered completely unacceptable.

The stove corner was considered a dirty place, in contrast to the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always sought to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz or colored homespun, a tall cabinet or a wooden partition. The corner of the stove, thus closed, formed a small room called a “closet”. The stove corner was considered an exclusively female space in the hut. During the holiday, when many guests gathered in the house, a second table was placed near the stove for women, where they feasted separately from the men sitting at the table in the red corner. Men, even their own families, could not enter the women’s quarters unless absolutely necessary. The appearance of a stranger there was considered completely unacceptable.

During the matchmaking, the future bride had to be in the stove corner all the time, being able to hear the entire conversation. She emerged from the corner of the stove, smartly dressed, during the bride's ceremony - the ceremony of introducing the groom and his parents to the bride. There, the bride awaited the groom on the day of his departure down the aisle. In ancient wedding songs, the stove corner was interpreted as a place associated with the father's house, family, and happiness. The bride's exit from the stove corner to the red corner was perceived as leaving home, saying goodbye to it.

At the same time, the corner of the stove, from which there is access to the underground, was perceived on a mythological level as a place where a meeting of people with representatives of the “other” world could take place. According to legend, a fiery serpent-devil can fly through a chimney to a widow yearning for her dead husband. It was generally accepted that on especially special days for the family: during the baptism of children, birthdays, weddings, deceased parents - “ancestors” - come to the stove to take part in an important event in the lives of their descendants.

The place of honor in the hut - the red corner - was located diagonally from the stove between the side and front walls. It, like the stove, is an important landmark of the interior space of the hut and is well lit, since both of its constituent walls had windows. The main decoration of the red corner was a shrine with icons, in front of which a lamp was burning, suspended from the ceiling, which is why it was also called “saint”.

They tried to keep the red corner clean and elegantly decorated. It was decorated with embroidered towels, popular prints, and postcards. With the advent of wallpaper, the red corner was often pasted over or separated from the rest of the hut space. The most beautiful household utensils were placed on the shelves near the red corner, and the most valuable papers and objects were stored.

They tried to keep the red corner clean and elegantly decorated. It was decorated with embroidered towels, popular prints, and postcards. With the advent of wallpaper, the red corner was often pasted over or separated from the rest of the hut space. The most beautiful household utensils were placed on the shelves near the red corner, and the most valuable papers and objects were stored.

All significant events family life was noted in the red corner. Here, as the main piece of furniture, there was a table on massive legs on which runners were installed. The runners made it easy to move the table around the hut. It was placed near the stove when baking bread, and moved while washing the floor and walls.

It was followed by both everyday meals and festive feasts. Every day at lunchtime the whole peasant family gathered at the table. The table was of such a size that there was enough space for everyone. In the wedding ceremony, the matchmaking of the bride, her ransom from her girlfriends and brother took place in the red corner; from the red corner of her father's house they took her to the church for the wedding, brought her to the groom's house and took her to the red corner too. During the harvest, the first and last compressed sheaf was solemnly carried from the field and placed in the red corner.

"The first compressed sheaf was called the birthday boy. Autumn threshing began with it, straw was used to feed sick cattle, the grains of the first sheaf were considered healing for people and birds. The first sheaf was usually reaped by the eldest woman in the family. It was decorated with flowers, carried into the house with songs and placed in the red corner under the icons." The preservation of the first and last ears of the harvest, endowed, according to popular beliefs, with magical powers promised well-being for the family, home, and entire household.

Everyone who entered the hut first took off his hat, crossed himself and bowed to the images in the red corner, saying: “Peace to this house.” Peasant etiquette ordered a guest who entered the hut to remain in half of the hut at the door, without going beyond the womb. Unauthorized, uninvited entry into the “red half” where the table was placed was considered extremely indecent and could be perceived as an insult. A person who came to the hut could only go there at the special invitation of the owners. The most dear guests were seated in the red corner, and during the wedding - the young ones. On ordinary days, the head of the family sat at the dining table here.

The last remaining corner of the hut, to the left or right of the door, was the workplace of the owner of the house. There was a bench here where he slept. A tool was stored in a drawer underneath. In his free time, the peasant in his corner was engaged in various crafts and minor repairs: weaving bast shoes, baskets and ropes, cutting spoons, hollowing out cups, etc.

Although most peasant huts consisted of only one room, not divided by partitions, an unspoken tradition prescribed certain rules of accommodation for members of the peasant hut. If the stove corner was the female half, then in one of the corners of the house there was a special place for the older married couple to sleep. This place was considered honorable.

Shop

Most of the “furniture” formed part of the structure of the hut and was immovable. Along all the walls not occupied by the stove, there were wide benches, hewn from the largest trees. They were intended not so much for sitting as for sleeping. The benches were firmly attached to the wall. Other important furniture were benches and stools, which could be freely moved from place to place when guests arrived. Above the benches, along all the walls, there were shelves - “shelves”, on which household items, small tools, etc. were stored. Special wooden pegs for clothes were also driven into the wall.

An integral attribute of almost every Saitovka hut was a pole - a beam embedded in the opposite walls of the hut under the ceiling, which in the middle, opposite the wall, was supported by two plows. The second pole rested with one end against the first pole, and with the other against the pier. In winter, this structure served as a support for the mill for weaving matting and other auxiliary operations associated with this craft.

spinning wheel

Housewives were especially proud of their turned, carved and painted spinning wheels, which were usually placed in a prominent place: they served not only as a tool of labor, but also as a decoration for the home. Usually, peasant girls with elegant spinning wheels went to “gatherings” - cheerful rural gatherings. The “white” hut was decorated with homemade weaving items. The bedcloth and bed were covered with colored curtains made of linen fiber. The windows had curtains made of homespun muslin, and the window sills were decorated with geraniums, dear to the peasant’s heart. The hut was cleaned especially carefully for the holidays: women washed with sand and scraped white with large knives - “mowers” - the ceiling, walls, benches, shelves, floors.

Peasants kept their clothes in chests. The greater the wealth in the family, the more chests there are in the hut. They were made of wood and lined with iron strips for strength. Often chests had ingenious mortise locks. If a girl grew up in a peasant family, then from an early age her dowry was collected in a separate chest.

A poor Russian man lived in this space. Often in the winter cold, domestic animals were kept in the hut: calves, lambs, kids, piglets, and sometimes poultry.

The decoration of the hut reflected the artistic taste and skill of the Russian peasant. The silhouette of the hut was crowned with a carved

ridge (ridge) and porch roof; the pediment was decorated with carved piers and towels, the planes of the walls were decorated with window frames, often reflecting the influence of city architecture (Baroque, classicism, etc.). The ceiling, door, walls, stove, and less often the outer pediment were painted.

Non-residential peasant buildings made up the household yard. Often they were gathered together and placed under the same roof as the hut. They built a farm yard in two tiers: in the lower one there were barns for cattle and a stable, and in the upper one there was a huge hay barn filled with fragrant hay. A significant part of the farm yard was occupied by a shed for storing working equipment - plows, harrows, as well as carts and sleighs. The more prosperous the peasant, the larger his household yard was.

Non-residential peasant buildings made up the household yard. Often they were gathered together and placed under the same roof as the hut. They built a farm yard in two tiers: in the lower one there were barns for cattle and a stable, and in the upper one there was a huge hay barn filled with fragrant hay. A significant part of the farm yard was occupied by a shed for storing working equipment - plows, harrows, as well as carts and sleighs. The more prosperous the peasant, the larger his household yard was.

A bathhouse, a well, and a barn were usually placed separately from the house. It is unlikely that the baths of that time were very different from those that can still be found now - a small log house,

sometimes without a dressing room. In one corner there is a stove-stove, next to it there are shelves or shelves on which they steamed. In another corner is a water barrel, which was heated by throwing hot stones into it. Later, cast iron boilers began to be installed in stoves to heat water. To soften the water, wood ash was added to the barrel, thus preparing lye. The entire decoration of the bathhouse was illuminated by a small window, the light from which was drowned in the blackness of the smoky walls and ceilings, since in order to save wood, the bathhouses were heated “black” and the smoke came out through the slightly open door. On top, such a structure often had an almost flat pitched roof, covered with straw, birch bark and turf.

The barn, and often the cellar underneath it, was placed in plain sight opposite the windows and away from the dwelling, so that in the event of a hut fire, a year's supply of grain could be preserved. A lock was hung on the barn door - perhaps the only one in the entire household. In the barn, in huge boxes (bottom boxes), the main wealth of the farmer was stored: rye, wheat, oats, barley. It’s not for nothing that they used to say in the villages: “What’s in the barn is what’s in the pocket.”

QR code page

Do you prefer to read on your phone or tablet? Then scan this QR code directly from your computer monitor and read the article. To do this, any “QR code scanner” application must be installed on your mobile device.